Vera and Donald Blinken Open Society Archives

Unintentional Effect: the 45th Anniversary of the Helsinki Accords

August 1 will mark the 45th anniversary of the Helsinki Accords, which, owing to its human rights principle, became a catalyst of the 1989 regime change.

Fidesz marching to the March 15th opposition commemoration in 1989, carrying the sign "Human Rights to the People."

Fidesz marching to the March 15th opposition commemoration in 1989, carrying the sign "Human Rights to the People."

(Photo: 1989.osaarchivum.org/Piroska Nagy)

The Blinken Open Society Archives, one of the world’s largest repositories of Cold War and human rights holdings, preserves documents that outline the history of demanding human rights in Hungary, from the Helsinki Accords to Charter 77 and to the "revolution under the rule of law" in 1989.

Initiated in 1973, the Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe was a series of negotiations that was concluded on August 1, 1975, 45 years ago, with the signing of the Helsinki Accords. Its fundamental objective was to promote international relations across the Cold-War divide between East and West. Signed by 35 countries, the Helsinki Final Act comprises four baskets that prescribe commitments and conditions to different kinds of co-operations. The third basket addressed humanitarian co-operations, detailing the requirements of relations among people, information and its dissemination, cultural co-operations and exchanges, and education.

More importantly, the agreement established primary principles that should guide co-operations, also including that "[t]he participating States will respect human rights and fundamental freedoms, including the freedom of thought, conscience, religion or belief."

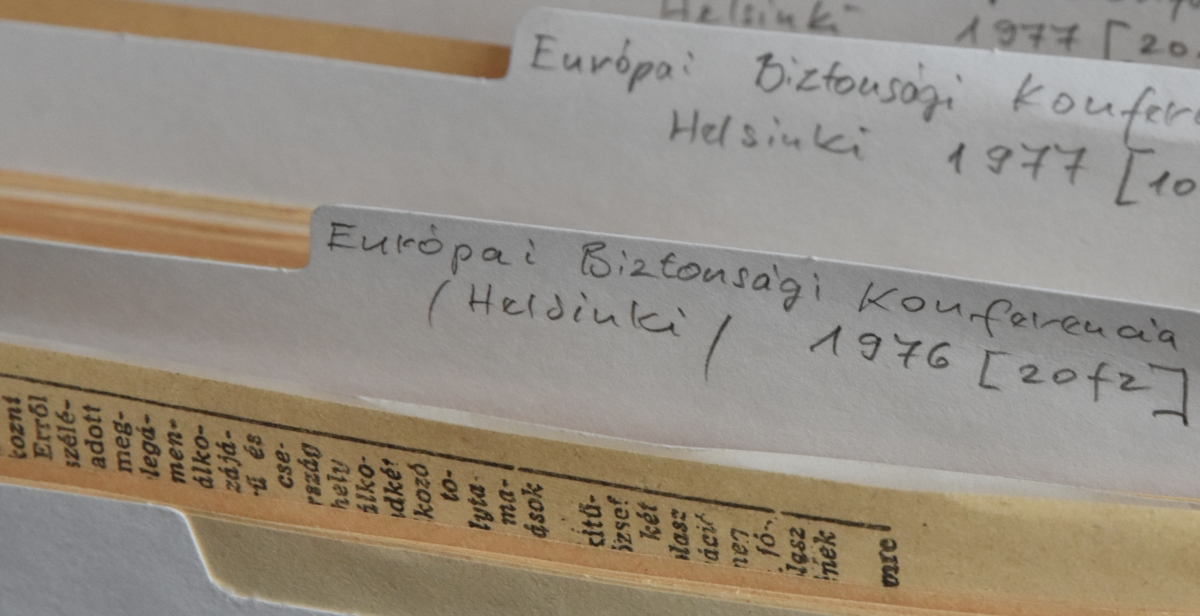

RFE Subject Files on the Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe at the Archives.

RFE Subject Files on the Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe at the Archives.

(Photo: Miklós Zsámboki)

Available at the Research Room, the Blinken OSA holds copies of the Final Act in several languages, transcripts of János Kádár's conference speech and an interview he gave to the Hungarian Television on site, the Subject Files compiled at the Radio Free Europe (RFE) Research Institute, or the task plan prepared at the Ministry of Interior.

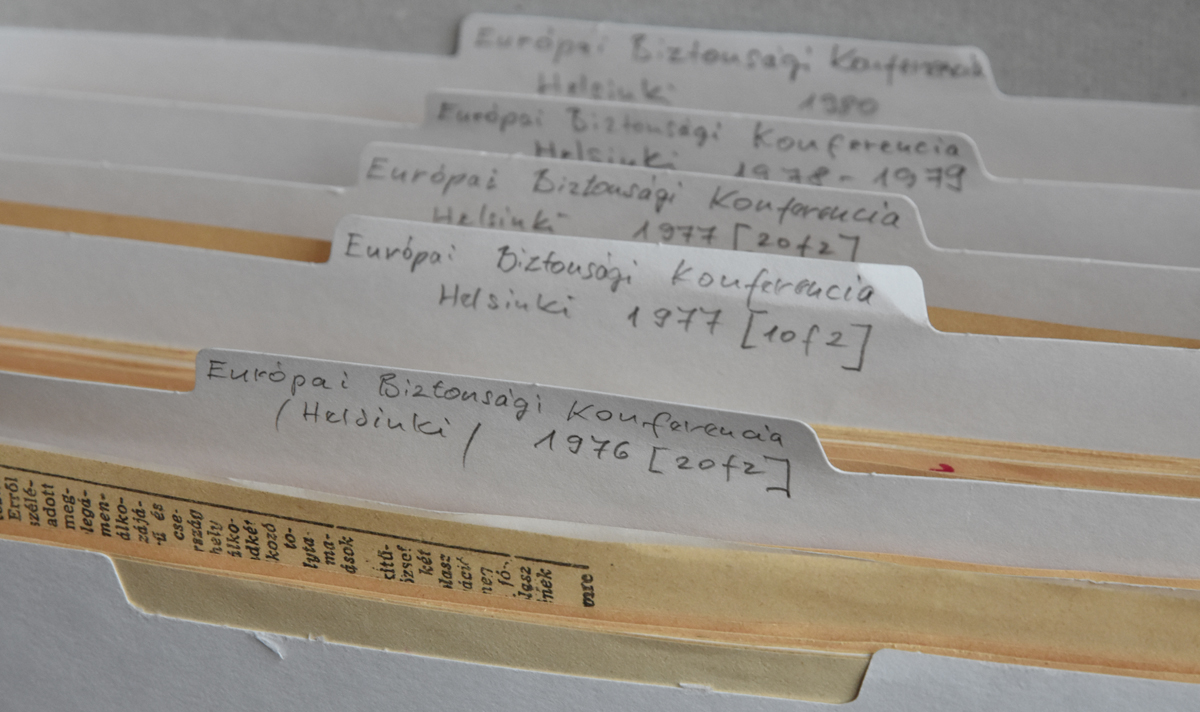

"Based on the contents of the Final Act, pressure to shut down hostile radio stations like Radio Free Europe must be heightened."

"Based on the contents of the Final Act, pressure to shut down hostile radio stations like Radio Free Europe must be heightened."

(Regulation of the Government of the Hungarian People's Republic, HU OSA 408-3-2,

László Varga Collection, Blinken OSA)

The Research Institute of RFE in Munich compiled thematic collections, so-called Subject Files related to specific issues, comprising press clippings, news agency releases, transcripts of state radio broadcasts. The Subject Files on the Helsinki conference, spanning 10 folders, reflect the public Hungarian stance on the Helsinki Accords from its signing until 1987. This can be expanded by the state security documents included in the László Varga Collection, like the task plan and the proposals drafted at the Ministry of Interior, or the regulations issued by the government. These documents provide a glimpse into how the Hungarian State interpreted the Helsinki Final Act, and especially how it was seen both as an opportunity and a threat.

"Capitalist states hope to exploit the opportunity provided by the free flow of ideas and people to launch an ideological offensive. State security must be aware that the Imperialists intend to capitalize on the contents of the Final Act in pursuing hostile endeavors."

"Capitalist states hope to exploit the opportunity provided by the free flow of ideas and people to launch an ideological offensive. State security must be aware that the Imperialists intend to capitalize on the contents of the Final Act in pursuing hostile endeavors."

(Task Plan with regards to the Final Act of the Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe,

HU OSA 408-3-2:5/3, László Varga Collection, Blinken OSA)

Evidently, the Hungarian State was mistrustful (or paranoid); however, researchers of the Final Act tend to question that the West had intentionally installed a trap within the Helsinki Accords. Their doubt is supported by the fact that the document did not involve sanctions, while the human rights principle was only the seventh out of the ten guiding principles; sovereign equality, peacefulness, and, especially, non-intervention in internal affairs were all principles of greater importance. In spite of this, the Helsinki Accords did become a vital instrument in the regime changes in Eastern Europe. It provided grounds for demanding human rights, putting pressure on the states of the Eastern Bloc as well as of the West; while the previous became accountable for human rights violations, the latter for turning a blind eye to these.

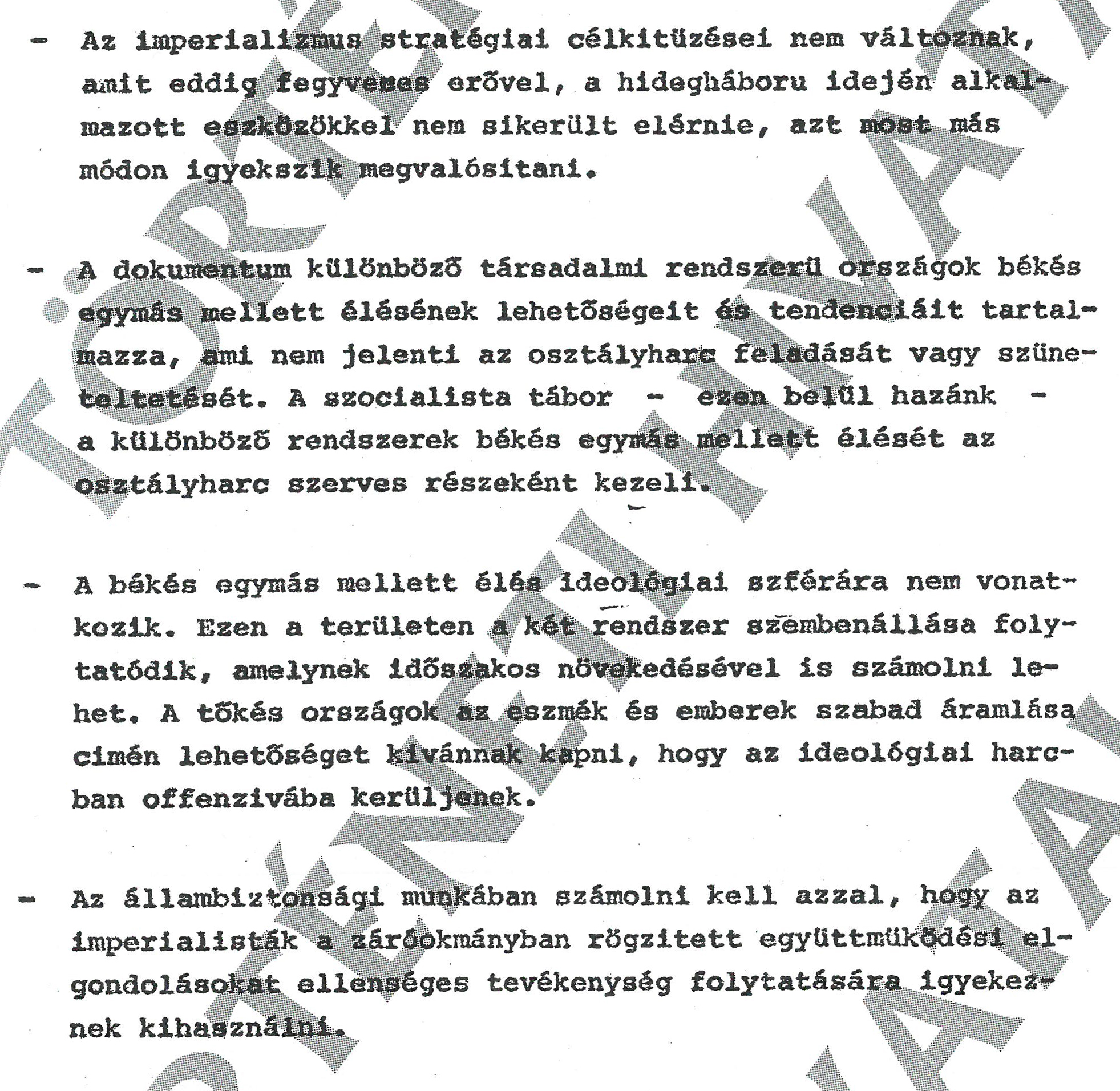

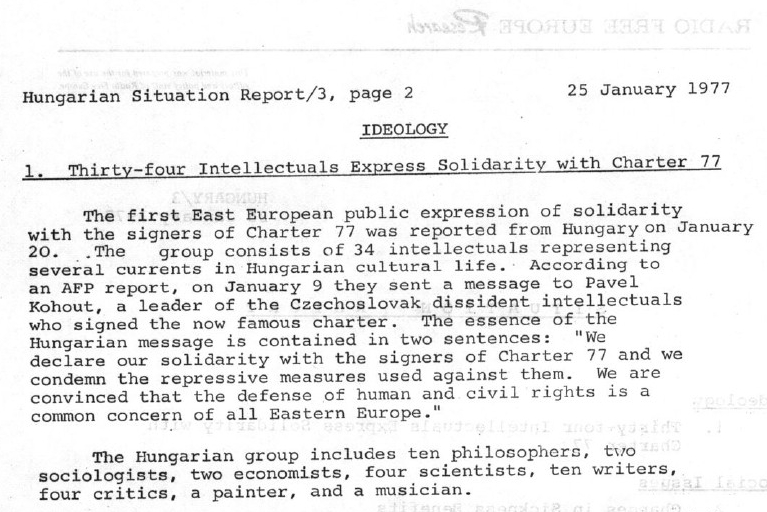

In 1976, the year after the Helsinki Accords was signed, the Moscow Helsinki Group was formed in the USSR, soon followed by similar groups throughout the country. The Workers' Defence Committee was established in Poland, and signatures were collected in Czechoslovakia reinforcing a political text. In January 1977, the text entitled Charter 77 was published in Western journals and read out on Radio Free Europe, as a result of which an authentic copy is preserved at Blinken OSA. Signed by 243 individuals, Charter 77 protested the violations of the very human rights recorded in the Final Act. The organizers were detained and imprisoned, which sparked Hungarian intellectuals to take a stand by issuing a two-sentence long statement of solidarity saying, "We declare our solidarity with the signers of Charter 77 and we condemn the repressive measures used against them. We are convinced that the defense of human and civil rights is a common concern of all Eastern Europe." In secret, 34 signatures were collected in support of the statement then sent out to the journal Le Monde. The RFE Situation Report on the case is accessible in the Archive's Digital Repository:

Situation Report: Hungary, 25 January 1977

Situation Report: Hungary, 25 January 1977

(HU OSA 300-8-47-108-3; Records of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty Research Institute, Blinken OSA)

András Mink's reader and András Bozóki's 2019 book Gördülő rendszerváltás both begin the chronology of the regime change process with this political act. According to János Kis, "the typewritten samizdat was a result of the 1977 declaration," also creating the so-called secondary publicity, and with it the democratic opposition; which, therefore, was founded on the grounds of human rights, weaponizing the "provocative exercising" and public demanding of those rights. Or, as the Situation Report put it:

Situation Report: Hungary, 25 January 1977

Situation Report: Hungary, 25 January 1977

(HU OSA 300-8-47-108-3, Records of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty Research Institute, Blinken OSA)

Encouraged by the Helsinki Accords, the (risky) activity of newly established initiatives throughout Eastern Europe primarily involved the documentation of and protest against human rights violations, raising awareness in the West. As apparent in the Hungarian expression of solidarity, instead of isolated groups, they composed an international movement, later dubbed human rights movement or Helsinki movement. From 1978, the separate organizations were coordinated by the Helsinki Watch, which eventually evolved into the International Helsinki Federation for Human Rights (IHF, see its history here). Blinken OSA became the official archives of IHF in 1998, thus the complete archives of IHF is preserved here, with, for example, reports, press clippings, investigations compiled according to countries as well as to high-profile cases, or the documentations of missions, trainings, and conferences, such as the 1985 Unofficial Cultural Symposium, organized by the IHF in Budapest.

Unofficial Cultural Forum, Budapest, 1985. With, among others, the recently passed away Mária M. Kovács.

Unofficial Cultural Forum, Budapest, 1985. With, among others, the recently passed away Mária M. Kovács.

(HU OSA 318-0-9; Records of the International Helsinki Federation for Human Rights, Blinken OSA)

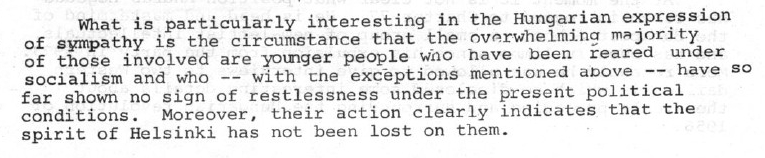

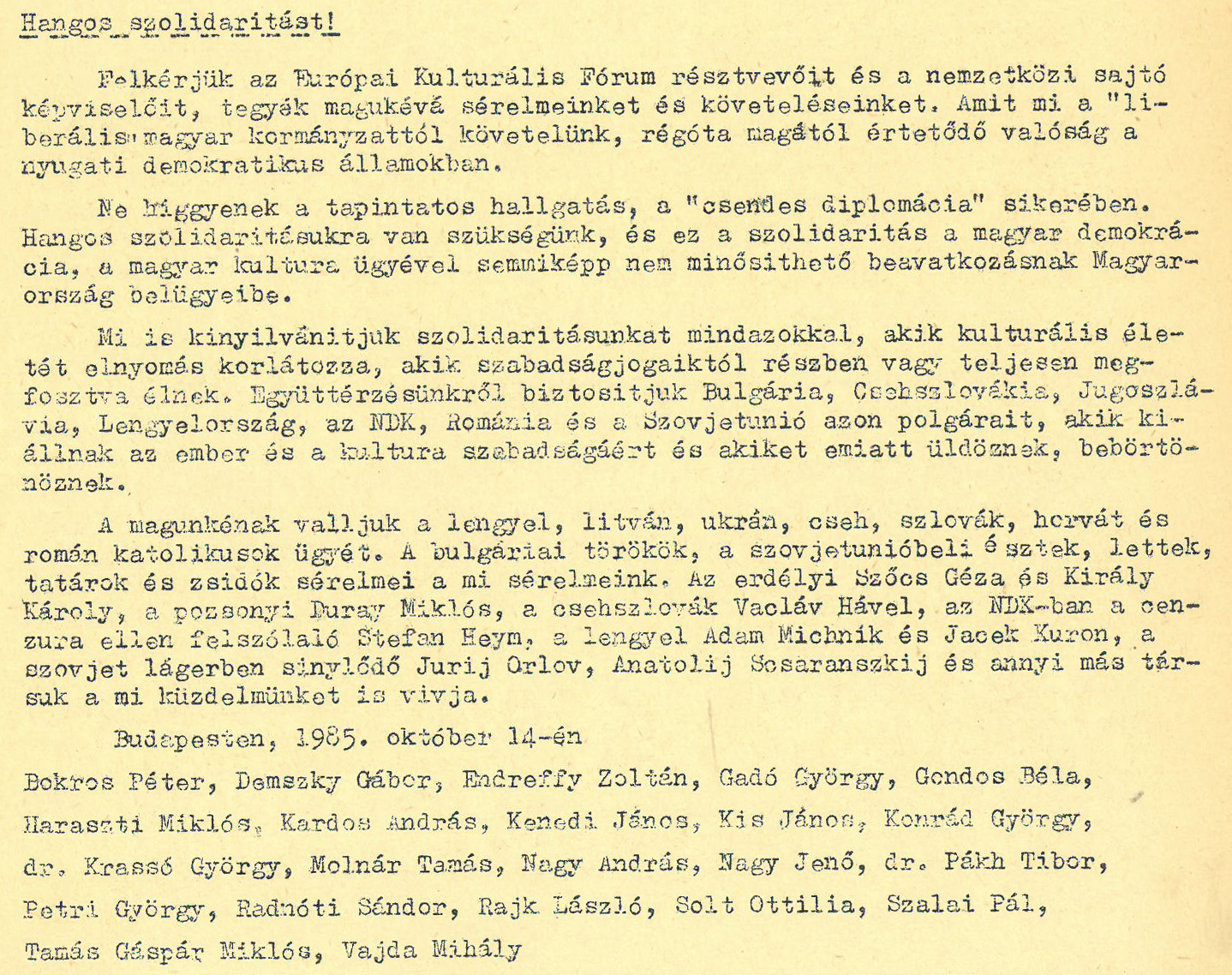

In 1985, on the 10th anniversary of the Helsinki Accords, Budapest hosted the European Cultural Symposium, a formal diplomatic event addressing the efficacy of the third (humanitarian) basket of the Helsinki Accords. The IHF organized a counter-symposium, the Unofficial Cultural Symposium, attended, besides Hungarian intellectuals, by the likes of Susan Sontag, Danilo Kiš, or Pavel Kohout. The Hungarian authorities in the last moment banned the counter-symposium, which then took place in private apartments. Exploiting the international attention, prominent figures of the Hungarian democratic opposition issued an appeal objecting the presumption that human rights violations in Hungary were over, expressing subtle criticism of the Final Act as well. Owing to IHF, the text was handed out and partly read out also at the parallel "discreet" diplomatic event; the Lajos Jakab Samizdat Collection holds a typewritten original of the appeal, which later was published in the samizdat journals Beszélő and Hírmondó, and also in the official publication of the Unofficial Symposium, among the conference lectures, in English.

"Do not have faith in the eventual success of discreet silence and 'quiet diplomacy.' We need unquivocal expressions of solidarity and such solidarity with the cause for of Hungarian democracy and culture can in no way be seen as interference in the internal affairs of Hungary. We ourselves are in solidarity with all people whose cultures are oppressed, wo are partially of totally deprived of their rights."

(Appeal by the Hungarian Democratic Opposition, October 14, 1985, HU OSA 426-0-4:2/11, Lajos Jakab Samizdat Collection, Blinken OSA)

Demanding human rights constitued a constant part of the process leading to the regime change in Hungary. On March 15, in an emblematic moment of the year 1989, the 12 points democratic organizations and parties had agreed on as common demands were read out by actor György Cserhalmi in front of hundreds of thousands.

The second point called for the rule of law and human rights, the third for the freedom of expression, of the press, of thought, and of education, the fourth for the right to strike and for the freedom of advocacy, of demand, and of solidarity, while the fifth for the basic conditions to a dignified life.

Also in 1989, the Hungarian Helsinki Committee was established on May 19, and remains active today.

György Cserhalmi reading out the 12 points.

(The People Demand, a film by the Black Box Foundation. The Black Box Foundation's documentary films are available at the Archive.)