Vera and Donald Blinken Open Society Archives

“We Do Not Want to Make that Mistake Again” – When the West Did Not Trust the Soviet Union

British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher traveled to the Soviet Union in March 1987; it was her first official visit to Moscow since in office for seven years, and she was the first UK leader to visit the USSR in 12 years. The event was closely followed by the press on both sides of the Iron Curtain, as a result of which the Records of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty Research Institute, preserved at the Blinken Open Society Archives at CEU, comprises numerous press agency releases, Eastern and Western press reports and analyses. Mostly incorporated into the several Subject Files on Margaret Thatcher, they allow us to reconstruct this historical episode.

British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher traveled to the Soviet Union in March 1987; it was her first official visit to Moscow since in office for seven years, and she was the first UK leader to visit the USSR in 12 years. The event was closely followed by the press on both sides of the Iron Curtain, as a result of which the Records of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty Research Institute, preserved at the Blinken Open Society Archives at CEU, comprises numerous press agency releases, Eastern and Western press reports and analyses. Mostly incorporated into the several Subject Files on Margaret Thatcher, they allow us to reconstruct this historical episode.

Shortly before the visit, Soviet Secretary General Mikhail Gorbachev announced his willingness to negotiate the disarmament of medium-range nuclear weapons in Europe. Thatcher, however, maintained that as long as the Soviet Union was seen as a threat, and the West could not trust the USSR, peace could only be guaranteed by nuclear deterrence.

The 1987 Thatcher–Gorbachev meeting in Moscow on the front page of Pravda the next day.

The 1987 Thatcher–Gorbachev meeting in Moscow on the front page of Pravda the next day.

(Blinken OSA Library)

In Thatcher’s honor, a dinner and a banquet was held in the Kremlin on March 30. Here, the British Prime Minister had the opportunity to explain in a public speech that if Europe completely removed its medium-range weapons, it would be defenseless against the massive superiority of the short-range arsenal of Warsaw Pact countries. For this reason, while arguing for balance and a gradual disarmament, she placed great emphasis on trust, which she linked to human rights. As she laid it out, the more the Soviet Union met human rights requirements (in, for example, releasing political prisoners), “the greater the readiness you will find in the West to believe that peaceful and friendly relations with the Soviet Union can be maintained and extended.” She specifically addressed the situation in Afghanistan, under Soviet occupation since 1979, noting that whether the Soviet Union withdrew its troops from Afghanistan or not, would show if other countries had to “trust or fear you.”

During her stay in Moscow, Thatcher met with Nobel Prize-winning Russian dissident Andrei Sakharov, as well as Jewish dissident and refusenik Josef Begun; both had regained their freedoms just months earlier, after years of political persecution. The fact that the English side initiated these meetings and the Soviet apparatus allowed them, was indicative in both directions; and at the same time Thatcher could learn about the human rights situation in the Soviet Union from authentic sources. With Gorbachev himself she had several meetings, amounting to approximately nine hours. Not much detail was revealed at the time, but based on her statements, the Western press found that the British Prime Minister was convinced by the glastnost (openness) program announced by Gorbachev.

Today, the minutes of the Thatcher–Gorbachev conversations are public, so we know that Thatcher here was even more straightforward about the lack of trust toward the Soviet Union:

Gorbachev: In a word, what is that “damned Russian bear” planning to do?

Thatcher: I just want you to know how we feel. Once we misjudged your actions in relation to Czechoslovakia. We thought that you would not invade, because it would damage your prestige in the world. But we were wrong. We do not want to make that mistake again.

While this is only a minor segment of the conversations that at the time were called friendly and productive, it may have had a major effect on Gorbachev. According to the minutes of a Politburo Session a few months later, what he had heard from Thatcher helped Gorbachev understand the alertness of Western leaders and Western society in general: it is likely that these discussions also contributed to his attempts at dismantling the image of the aggressor the West had of the Soviet Union, and at earning the trust of the West. International trust was absolutely necessary for the reforms of perestroika (restructuring), the transformation and opening of the closed Soviet economy on its way to collapse.

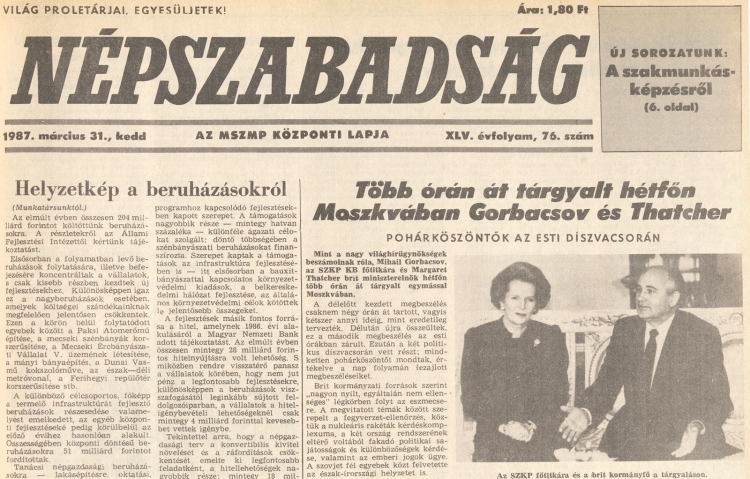

The 1987 Thatcher–Gorbachev meeting in Moscow on the front page of the Hungarian party daily Népszabadság (People's freedom) the next day.

The 1987 Thatcher–Gorbachev meeting in Moscow on the front page of the Hungarian party daily Népszabadság (People's freedom) the next day.

(Blinken OSA Library)

In fact, Thatcher’s visit (and granting the freedom of Sakharov and Begun, and later others as well) may have already been part of that attempt. Instead of her speeches and press events, it was her televised interview, watched by millions of Soviet viewers, that received the most attention. During the 50-minute discussion with three top journalists, Thatcher expressed herself in first-person plural, as if representing the West. On Soviet state television, she explained in detail not only her reasons to consider destructive nuclear weapons to be the guarantee to peace, but also how the Soviet Union’s ceaseless threat was actually fueling armament, while “since the First World War, which finished in 1918, there has been no case where one democracy has attacked another. That is why we believe in democracy.“ She further elaborated on Western-style democracy, highlighting such extraordinary features as the fact that as prime minister she had to answer questions in parliament and on the radio without knowing in advance what those questions would be.

We are able to publish the TV interview because Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty in Munich, beside printed press and radio, also monitored Soviet television from 1985, thus taping this program as well. Prior to broadcast, the interview was edited, and instead of a live interpreter, it was presented with Russian voice-over. Since the staff at RFE/RL was able to make an English translation of the Russian voice-over, the subtitle of the copy uploaded now to the Blinken OSA YouTube Channel was synched not to Thatcher’s voice, but to the voice-over’s. Furthermore, since the translation itself is a source document, we did not correct potential errors.

The voice-over’s transcript allows us to follow the differences, sometimes smaller, sometimes larger, between what Thatcher said and what Soviet viewers were told. Furthermore, the Margaret Thatcher Foundation has since then made the exact transcript of the original English public. In one case, for example, while the Russian voice-over is silent, Thatcher’s argument for the logic of the nuclear deterrent is clear: “Does not the bully go for the weak person, not for the strong?" Similarly, the Russian goes silent when Thatcher strikes down at the marginal journalistic remark “we want to use all the advantages of the Socialist system for our restructuring.” Although it is not part of the voice-over, Thatcher’s quick question in response was included in the RFE/RL transcript: “Would you please say what that meant? You tossed out a quite provocative comment. What do you think are the advantages of a Socialist society?”

The Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty Research Institute produced a full report on the Soviet reception of the interview. According to this, the television received so many letters of complaint about the journalists’ failure, that they had to return to screen and practice “self-criticism.” They argued that the interview was “an unprecedented experiment by Soviet television in the field of glasnost,” which may have aroused disapproval because, in the spirit of the openness of glasnost, “no lecturer appeared after the interview with a briefcase and a pointer to explain to us what had been good and what bad.” However, RFE/RL analysts added that, presumably, “under the impact of the information revolution, the Soviet Union will be obliged in one way or another to try to direct the free flow of information into ‘regime-controlled channels.’ . . . The Soviet authorities are seeking, before it is too late, to ‘coopt’ information not to their liking that Soviet citizens will in any case obtain from other sources.”

Nevertheless, The Guardian quoted Moscow passers-by saying, “I think for the first time I understand why the West is so worried about us. Not that the West is right. We don’t want a war, but I see better now why you keep on guard.” Meanwhile, according to the New York Times summary on the Prime Minister’s Moscow visit, “Thatcher left carrying three messages for the Western allies,” most importantly, that “change is going in the direction of more openness. . . . Gorbachev can be trusted.”