Vera and Donald Blinken Open Society Archives

A Sharp, Accurate, Leftist Critic of 1989 – György Krassó Born 90 Years Ago

A man smoking cigarette on a bench, arguing with the journalist Henrik Havas, complains that “a fraudulent and brutally undemocratic electoral law has been drawn up in secret . . . with privileged groups calling themselves opposition.” This is Hungary not in the 2010s or 2020s, but in 1989, as put by György Krassó, one of the first critics of the regime change.

A man smoking cigarette on a bench, arguing with the journalist Henrik Havas, complains that “a fraudulent and brutally undemocratic electoral law has been drawn up in secret . . . with privileged groups calling themselves opposition.” This is Hungary not in the 2010s or 2020s, but in 1989, as put by György Krassó, one of the first critics of the regime change.

Krassó, who was born 90 years ago today, denounced the regime change not as a hard-line member of the ruling Communist party. He became the transition process’ most adamant critic from within the 1980s circle of opposition intellectuals; the opposition to the opposition, as he was often labelled. Still, he strived to not only judge but also practice politics: he founded the Hungarian October Party (Magyar Október Párt), which was at war with pre- and post-1989 elites at once. In a few months, they carried out some of the most entertaining events of the regime change period; statues were cast, streets renamed, headquarters occupied, and ballot papers burned.

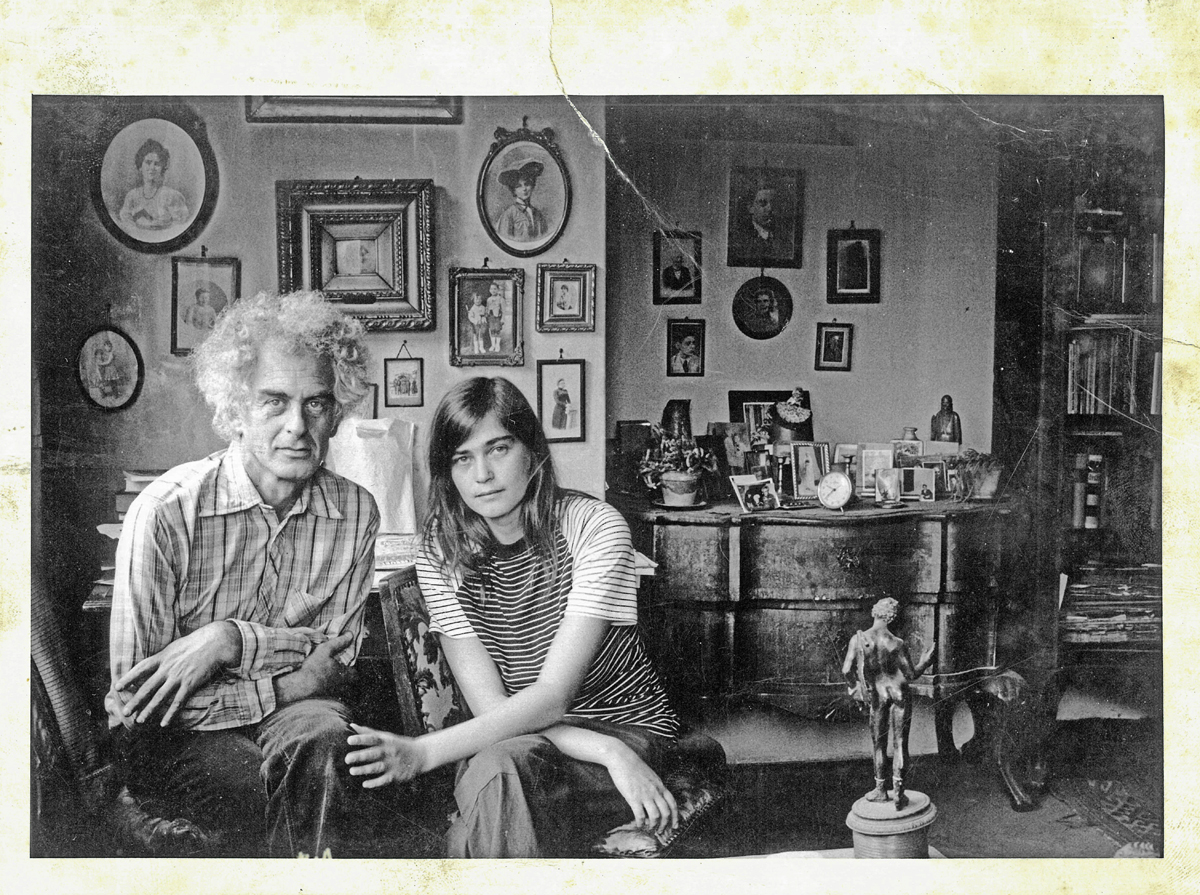

György Krassó and Ágnes Háy in 1984.

(HU OSA 362 Tibor Philipp Collection, Photos and Negatives)

Be that as it may, Krassó had, for long, followed the same path as the urban intellectuals of the transition process. After the Second World War, he joined the Hungarian Communist Party in 1947—when he was only 15—in the hope, as he later put it, that “based on Marxist ideals, we could build a new, free world with no exploitation.” Like many of his intellectual contemporaries who quickly and enthusiastically joined State Socialism, Krassó participated in the building of the new system with full faith. However, he found his place not in the state apparatus or the party bureaucracy, but in the Mátyás Rákosi Iron and Metal Works in Csepel, where he spent two years at his own request, because he felt that “one cannot be a good communist, one cannot fight successfully for the party’s objectives, if one has no contact with the workers, does not know them, has not lived among them.”

Then came the university years at the Karl Marx University of Economic Sciences, during which he was expelled first from the party and then from the university before graduating. These clashes in the 1950s foreshadowed Krassó’s future participation in the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, with a weapon in hand, too, but mainly with a mimeograph, after which he spent seven years in prison. The experience of the revolution defined him until his death. To the end of his life, he pursued what he believed to had been the essence of 1956: workers’ democracy and workers’ self-government. For him, the 1956 of the workers’ councils was the real 1956. Workers’ councils embodied direct—in today’s terms, grassroots—democracy. Their aim was not to limit the idea of democracy to electoral systems, but to organize production, too, democratically. The workers’ councils of 1956 stood by the same values, their slogan (“We won’t return factories, or lands!”) expressed that restoring Capitalist conditions was not among the revolution’s aims.

Emerging in the late 1970s, the Hungarian opposition movements were quickly joined by György Krassó. However, his belief in workers’ self-government and his sharp criticism—that did not spare opposition intellectuals either—soon estranged him from these circles. Still, Krassó continued to take part in the activity of the 1980s urban opposition, and founded a samizdat publishing house under the name of Magyar Október Szabadsajtó (Hungarian October free press). Although his political vision of a plebeian democracy that is not only anti-Communist but also anti-elitist in general, was fundamentally different from that of his allies, his intellectual background and the aura of his brother, a Lukács disciple, kept him in this milieu.

György Krassó at the March 15 commemoration jointly organized in 1990 by the Alliance of Free Democrats, the Fidesz, the Entrepreneurs' Party, and the Social Democratic Party of Hungary. Before the official speaches, Krassó encouraged the crowd to boycott the coming elections.

György Krassó at the March 15 commemoration jointly organized in 1990 by the Alliance of Free Democrats, the Fidesz, the Entrepreneurs' Party, and the Social Democratic Party of Hungary. Before the official speaches, Krassó encouraged the crowd to boycott the coming elections.

(HU OSA 440 Éva Kapitány’s Photo Archive, under processing at Blinken OSA)

As the prospect of political change gradually became more realistic, the gap between opposition intellectuals and Krassó widened. In 1985, for example, he clashed with György Konrád at the Alternative Forum, organized in opposition to the European Cultural Forum, a showcase propaganda event of official cultural diplomacy. Konrád propagated the “republic of literature” in the face of censorship, about which Krassó remarked that it “displayed a high degree of intellectual aristocracy. . . . As far as my friend György Konrád is concerned, an intellectual class must be established, and there exists a secret republic that the powerful police minister cannot enter. But his comparison is misleading. Because besides the minister, the working people cannot enter either. Who will work in this republic? Who will make ends meet? Whose interests will this class represent?” At this point in the debate, Susan Sontag, who was also present, allegedly assured Krassó that he needed not to worry because, having been a samizdat intellectual, he was part of the “republic of literature”; which did not particularly impress Krassó.

It was not simply his personality that made his relationship with the urban opposition troublesome. Their conflicts were rather caused by the fact that while the opposition moved from Marxist philosophy toward liberal thinking, Krassó was a left-wing populist, thus they sought different political agendas. Nevertheless, the technocrats of the ruling communist party laying the groundwork for Capitalism in the name of Reformist Socialism, were even further away from him. Krassó repeatedly called himself an anti-communist, and at the same time was consistent in advocating a Leftist vision. His political ideas always returned to the workers’ councils of 1956, to the democratic organization of production. Not only did he translate Bill Lomax’s book on 1956, he made corrections and added footnotes based on his own experiences. Krassó’s sympathy for the oppressed classes did not stop at the level of theories; from the early 1980s on, he mentored the members of the Inconnu artistic group, who had numerous confrontations with the regime but were insecure when it came to the intellectual opposition milieu in Budapest.

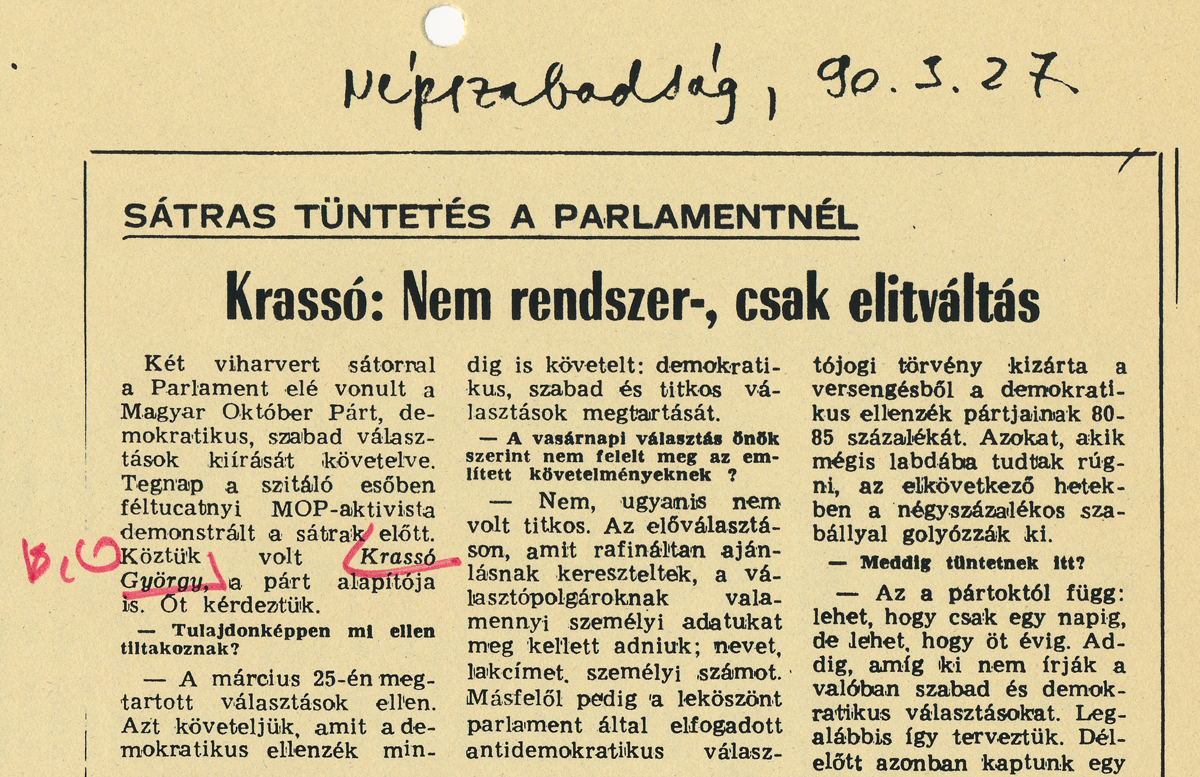

“Krassó: Not a change of regime, but of elites.” Press clipping from 1990, reporting on a protest Krassó organized in front of the Hungarian Parliament right after the first round of the first post-1989 elections.

(HU OSA 300 Records of RFE/RL Research Institute, Hungarian Unit, Biographical Files)

What prevented the relationship between Krassó and the Hungarian opposition from escalating was that he emigrated to London with his partner, the artist Ágnes Háy. After his years in London, he returned home in 1989, equipped with a completely new set of tools, but his political ambitions unchanged. He found that despite the political changes, “the people have no power at their hands.” The two years from 1989 until his death in 1991 became perhaps Krassó’s best-known period; instead of publishing books (for which, he said, he had no time anymore), he founded the Hungarian October Party (HOP), with which he carried out the most entertaining political actions of the transition period, which, at the same time, also were the most critical of the regime change process. The performance-like, trashy scenes contrasted sharply with the emblematic events of 1989. The style Krassó adopted—commemorating the 1956 Revolution with a plastic machine gun around his neck, or trying to rearrange the Red Star on Clark Ádám Square into a red circle—was equally distant from the carefully choreographed events of the regime change, such as the reburial of Imre Nagy, and from the declarations intellectual politicians expressed either in pamphlets or TV debates. These street actions, which András Bozóki called happenings already in 1989, may have been inspired by Ágnes Háy’s interest in metropolitan folklore, the provocative performances of the Inconnu Group, and the anti-Thatcher protest culture Krassó got to know in London, which mobilized far more spectacular tools, than the Hungarian opposition.

György Krassó in 1989 talking to the workers of the Csepel Works, his former workplace, at a political event organized by the Hungarian October Party.

(HU OSA 440 Éva Kapitány’s Photo Archive, under processing at Blinken OSA)

HOP members sang their marching song to the tune of Popeye the Sailor, and handed out bread and butter in front of Krassó’s former workplace, the Csepel Works. The action was a moderate success; news footage shows that the workers disapproved of a non-worker ranting about workers’ interests, as well as of the fact that Krassó’s anti-Sovietism had little to do with their daily livelihood problems. According to photographs preserved at Blinken OSA, the HOP event on August 20, 1989, did not move larger crowds either. Here, they demanded a Gypsy television, and staged the National Round Table Negotiations (the talks between opposition parties and the Hungarian Socialist Workers’ Party), in a fairground spectacle. The latter revolved around a character representing the standard of living, which had nothing to do but sink; and for 5 HUF, visitors could throw balls at the puppets impersonating leading (Communist as well as opposition) politicians.

Krassó became truly famous after he renamed the street named since 1968 after Ferenc Münnich, who had played an decisive role in post-1956 repression, to its former name, and also organized the removal of the statue of Münnich on Honvéd Square. These actions brought together all the characteristics of Krassó’s politics around 1989. Firstly, the Hungarian October Party was rather Krassó’ss one-man party, and its affairs were Krassó’s personal affairs. For instance, the Ferenc Münnich Street was renamed not only because of the political legacy of its namesake (many streets named after communist politicians could have been found), but also because Krassó happened to live on that very street. Secondly, these events can easily be seen as re-enactments of his own 1945–1956 political activism, from toppling statues to agitating in factory gates; as if Krassó in 1989 reached back to his own former tools. Thirdly, Krassó’s actions were more angry rants against the regimes before and after 1989, than attempts at building a popular force out of the losers of those regimes. Although Krassó, a bohemian and extroverted plebeian leftist commuting between Budapest and London, was sharply and accurately critical of the Hungarian regime change, he was unable to organize “his people,” so that the Hungarian October Party would be “the party of the street” not only in its name and program.

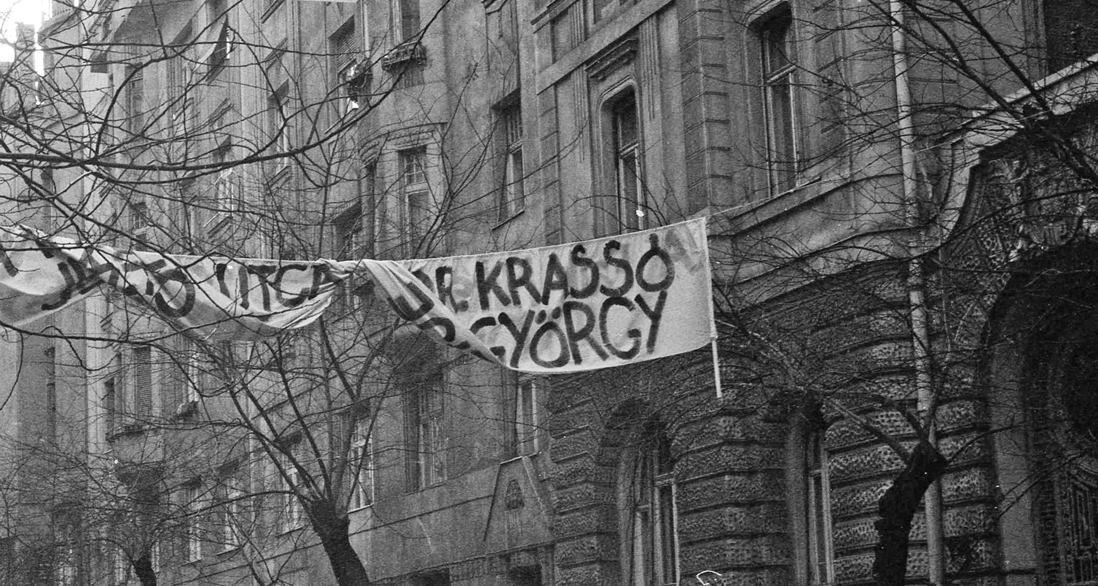

Banner of the Hungarian October Party, “the party of the street,” above Falk Miksa Street (leading to the Hungarian Parliament).

(HU OSA 440 Éva Kapitány’s Photo Archive, under processing at Blinken OSA)

Already during the regime change period, Krassó stood by the losers of the transition, and against the elites before and after 1989; behind his loudly proclaimed anti-Communism, a Leftist anger was at work. When, after a series of heart attacks, he passed away in 1991, his funeral was attended by those he could not organize. As Ferenc Kőszeg said that day, in the midst of the reparations debates following 1989, “Those who came were primarily . . . those who were hardly interested in the reparation issue, because they never had anything to take away from them, neither in 1938 nor in 1949.”