Vera and Donald Blinken Open Society Archives

A Spy or Not a Spy: New Perspectives on the Most Famous Polish Spy Story through the Lens of Free Europe Committee/Radio Free Europe

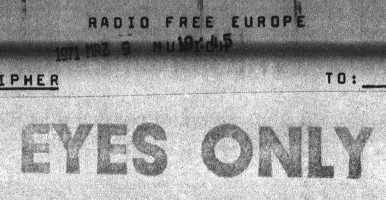

The digitization of documents leaves those who study history without the charm of digging into the dusty stacks of documents, but HU OSA 298, the new collection of Free Europe Committee (FEC) materials allows scholars to experience the James Bond spirit as they search through the "strictly confidential" ciphered messages. New documents published by the Vera and Donald Blinken Open Society Archives (Blinken OSA) offer more insights into the history of CIA-funded RFE from the late 1960s and early 1970s. Radio Free Europe started broadcasting in early 1949 as a part of the FEC and later became one of the cornerstones of anti-communist propaganda in Central-Eastern Europe.

The digitization of documents leaves those who study history without the charm of digging into the dusty stacks of documents, but HU OSA 298, the new collection of Free Europe Committee (FEC) materials allows scholars to experience the James Bond spirit as they search through the "strictly confidential" ciphered messages. New documents published by the Vera and Donald Blinken Open Society Archives (Blinken OSA) offer more insights into the history of CIA-funded RFE from the late 1960s and early 1970s. Radio Free Europe started broadcasting in early 1949 as a part of the FEC and later became one of the cornerstones of anti-communist propaganda in Central-Eastern Europe.

RFE gained particular importance during the 1956 revolution in Hungary by providing almost 24/7 coverage on the situation. Similarly, throughout the 60s it transmitted information to the socialist block about political and social issues including the Cuban Crisis and the Prague Spring. By the end of the 60s, rumours of funding from the CIA spread and in 1971 the US government initiated the process of reorganization. Moreover, another great scandal tarnished the radio’s reputation when Andrzej Czechowicz, a member of the Polish board, disappeared and was revealed to be a spy a few days later. [1] New documents on this issue are now accessible to the public and show more of the inner RFE perspective on scandal.

OSA has been publishing materials from the Free Europe Committee collection from 1960 till 1973. A stack of over 30 thousand files includes reports and correspondence on financial issues, broadcasting, jamming, employment and reviews of the press on both sides of the Iron Curtain. This is the second part of the FEC/RFE Collection, which was published last year. Originally, the microfilm reels came from the Hoover Institution and were digitized by OSA . Most importantly, the originals were destroyed after being filmed, so the reels are the only copies of FCE documents left.

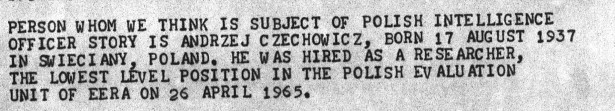

Andrzej Czechowicz was born in Święciany, Poland in 1937. After receiving a degree in History from the University of Warsaw he emigrated to the Federal Republic of Germany. Most probably, as suggested by Patryk Pleskot, Czechowicz left Poland simply in order to earn some money, not to work as a spy. Consequently, he won the status of political refugee. Before starting his job at RFE he was mainly helping in the refugee centers. As a result, he received his new documents in Germany. On 26 April 1965, he became a member of the Polish broadcasting team at RFE taking the "lowest position in the Polish evaluation unit… " [2] Later, Czechowicz received an American working visa and became eligible for citizenship under the terms of the Rodino Bill. [3] However, on 19 April 1970 he suddenly disappeared from the radio.

The original story of the mission is contested as it is doubtful whether Czechowicz was originally sent abroad as a spy. Having spent some time in Germany, he decided to return to Poland and wrote a request to the Military Liaison Mission in Berlin, which appeared to be an intelligence service headquarters at the same time. [4] As a result, Military Intelligence offered Czechowicz a deal [5] : if he found work at RFE and spent some time there providing useful information, he would be allowed to come back. Once again, the official version differs: Czechowicz claimed that he was hired to act as an agent after training and was intentionally sent to FRG as he was suitably qualified for that job. During his press conference in 1971 in Poland, Czechowicz stated that he had joined the Polish intelligence services immediately after graduating. His main task - according to what was said at the conference - was to identify all the Polish sources of the information for "ideological diversions" which were in contact with RFE. After all, it seems more plausible that the spy's "dangerous mission" was an improvisation with Czechowicz as a puppet, rather than a planned intelligence action.

The original story of the mission is contested as it is doubtful whether Czechowicz was originally sent abroad as a spy. Having spent some time in Germany, he decided to return to Poland and wrote a request to the Military Liaison Mission in Berlin, which appeared to be an intelligence service headquarters at the same time. [4] As a result, Military Intelligence offered Czechowicz a deal [5] : if he found work at RFE and spent some time there providing useful information, he would be allowed to come back. Once again, the official version differs: Czechowicz claimed that he was hired to act as an agent after training and was intentionally sent to FRG as he was suitably qualified for that job. During his press conference in 1971 in Poland, Czechowicz stated that he had joined the Polish intelligence services immediately after graduating. His main task - according to what was said at the conference - was to identify all the Polish sources of the information for "ideological diversions" which were in contact with RFE. After all, it seems more plausible that the spy's "dangerous mission" was an improvisation with Czechowicz as a puppet, rather than a planned intelligence action.

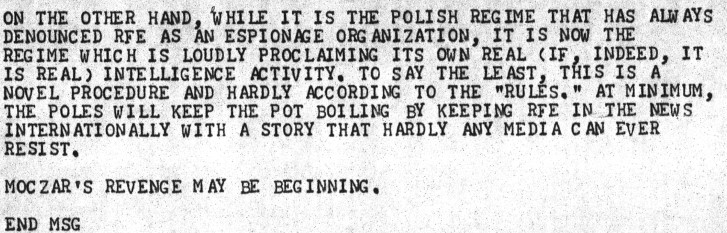

The new set of documents to be published by OSA sheds some light on the story from the RFE perspective. They show the inner reaction of the radio. In fact, the RFE Report prepared by Ralph E. Walter stressed the change in the traditional narrative describing RFE workers returning to their motherland. Usually, when Hungarians or Czechoslovaks went back home, the official media treated them as "unfortunates who had fled their homelands, sick of the terrible goings on [at RFE] , and decided to seek forgiveness from their peoples by going back…." Czechowicz story should have run along similar lines. However, as Walter mentions, the spy story was used to foment uncertainty among RFE staff, to arouse fear of RFE among Poles who were in Poland and to shatter confidence in RFE's Polish broadcasting. Finally, presenting Czechowicz as a successful spy meant showing the German public that if they went on collaborating with organisations potentially funded by the CIA, they would not be able to avoid public scandals connected to the intelligence services. The report itself is finished with "Moczar's revenge may be beginning. END MSG." , which referred to the attacks on the Polish First Secretary of the Party after the political crisis in March 1968. The official Polish People’s Republic narrative of a spy on a "dangerous mission" was a construct for the anti-RFE propaganda, which levelled severe criticism against the Polish government.

After "outing" himself, Captain Czechowicz became a star of the Polish media. During the official press conference, he regaled journalists with details about his stay in Munich. As well as a salary of 400 dollars [6] or circa 1600 German Marks, he also had all his accommodation expenses covered. Czechowicz criticized his former colleagues for not being able to act independently of the orders sent from the US. Additionally, he claimed to identify people who were providing RFE with information from Poland. Czechowicz emphasized that he himself felt good only after coming back to Poland and not during the "mission".

Obviously, there is one major flaw in the intelligence mission story: why would a country sacrifice a successful informer? Even if Czechowicz was a real spy, he could no longer continue his career. He went on giving interviews and lectures and later received a PhD. "Another aim was to exacerbate the Radio's problems both in Germany and in the United States" [7] : the disclosure of CIA funding led to criticism from senators Clifford Case and J. William Fulbright and to the establishment of the Board for International Broadcasting in October 1973. In addition, the KGB intelligence agent Oleg Tumanov joined Radio Liberty in 1966. We may hypothesize that it made no sense to keep the less skilled asset in the new entity, which was the RFE/RL.

To sum up, this story reveals the inner life of the structures involved in the information war between the PPR and RFE, not to mention West Germany and the US. The construction of myths about the Cold War period is clearly visible from different ideological camps. If you are interested in more insights from the FEC/RFE collections, feel free to visit the Blinken OSA website .

[1] This story is certainly not unique for either Radio Free Europe or Radio Liberty. Intelligence activity involving RFE/RL started as early as 1952. See, for example: Richard H. Cummings, Cold War radio: the dangerous history of American broadcasting in Europe, 1950-1989 (Jeffesron, N.C., 2009), 269-72.

[2] Munich crypto message #21 from March 9, 1971.

[3] The Rodino Bill was a legislative act that regulated the employment of legal and illegal aliens in the US in the late 60s – early 70s.

[4] A. Ross Johnson and R. Eugene Parta, eds., Cold War Broadcasting: Impact on the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe: A Collection of Studies and Documents (Budapest and New York, 2010), 190.

[5] Interview with Patryk Pleskot for the Institute of National Memory in Poland.

[6] Circa 2,426 USD in the 2017 equivalent.

[7] Johnson and Parta, Cold War Broadcasting , 194.