Vera and Donald Blinken Open Society Archives

Afterlives of the Murdered Poets – Radio Liberty on the Fate of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee

2022 marks the 70th anniversary of one of the most infamous events in post-WWII Soviet Jewish history. On the night between August 12 and 13, 1952, known as the Night of the Murdered Poets, 13 members of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee (JAC)—intellectuals, scientists, Yiddish poets and writers, all Soviet citizens of Jewish origin—were executed in Moscow’s Lubyanka prison. The victims were charged with espionage against the Soviet state and “nationalist activity,” which meant treason. Under arrest since the late 1940s, they were continuously interrogated and tortured, which made them falsely confess to their alleged crimes. Their execution in 1952, paired with the Doctors’ plot (a.k.a the case of saboteur doctors) and other alleged conspiracies of a disguised anti-Semitic campaign in the Soviet Union of 1948–1953, was a culmination of Stalinist persecution of Soviet Jews: their lives, their culture, and their position in the society.

2022 marks the 70th anniversary of one of the most infamous events in post-WWII Soviet Jewish history. On the night between August 12 and 13, 1952, known as the Night of the Murdered Poets, 13 members of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee (JAC)—intellectuals, scientists, Yiddish poets and writers, all Soviet citizens of Jewish origin—were executed in Moscow’s Lubyanka prison. The victims were charged with espionage against the Soviet state and “nationalist activity,” which meant treason. Under arrest since the late 1940s, they were continuously interrogated and tortured, which made them falsely confess to their alleged crimes. Their execution in 1952, paired with the Doctors’ plot (a.k.a the case of saboteur doctors) and other alleged conspiracies of a disguised anti-Semitic campaign in the Soviet Union of 1948–1953, was a culmination of Stalinist persecution of Soviet Jews: their lives, their culture, and their position in the society.

The Lubyanka Building in Moscow, housing the KGB and its prison where the arrested members of JAC were kept from 1948–1949 and executed on the night of August 12, 1952.

The Lubyanka Building in Moscow, housing the KGB and its prison where the arrested members of JAC were kept from 1948–1949 and executed on the night of August 12, 1952.

(Fortepan/Zsolt Dobóczi)

The attack against JAC soon after the end of WWII was rooted in the growing significance of the Committee among Soviet Jews and its authority in the West. Created in the early years of the war and supported by the government and Stalin, JAC successfully influenced international public opinion and lobbied world Jewry to support the USSR (politically and financially) in fighting Nazi Germany. In postwar years, the Committee documented Jewish resistance and Nazi crimes against Jews on Soviet territory. This, however, contradicted the official Soviet standing concerning the memory of the war, which emphasized heroism and suffering of the entire Soviet people, not any specific ethnic group. In total, 125 people were persecuted within the JAC case; 23 were shot, 6 died during investigations. Subsequently, all were rehabilitated, some in the mid-1950s, some in the late 1980s.

Radio Liberty press release on the special program for the execution’s 20th anniversary in 1972, with readings of poems by the murdered poets, and coverage of the commemorations in Europe, Israel, and the US.

(HU OSA 300-80-7, RFE/RL Research Institute, Soviet Red Archives, USSR Biographical Files)

The Night of the Murdered Poets became a memorial occasion in the West as early as the 1960s. Commemorations were continuously present throughout the Cold War period in the activities of international Jewish organizations, but also with the help of Radio Liberty; Radio Free Europe’s sister channel that broadcast from Munich to the Soviet Union in Russian reminded about the anniversary on a permanent basis. This execution gained such a significance for several reasons. First, due to its wartime activity, the Committee was not only known in the West, it was accepted as a representative body of Soviet Jews. Second, victims of the 1952 August killings also included five prominent Soviet Yiddish literary figures: Dovid Bergelson, Perets Markish, Itzik Fefer, Dovid Hofshteyn, and Leyb Kvitko. Originally from a region of modern-day Ukraine, they were members of the Kyiv Group that managed to survive Stalin’s Great Purge. These poets and writers not only embraced and were deeply rooted in the Soviet political project, they took an essential part in creating Soviet Yiddish culture. Thus, coupled with the 1948 assassination (staged as a car accident) of JAC chairman Solomon Mikhoels, actor and artistic director of the Moscow State Jewish Theater, the 1952 murder was seen in the West as a brutal attack against Yiddish literature and culture in general. Third, the commemorations were shaped by the larger context of the Cold War, and also by the struggle of Soviet Jews to emigrate (primarily) to Israel. Throughout the Cold War, the matter of Jewish emigration was highly political and often caused diplomatic tension, as captured in the unofficial but internationally recognized term refusenik; the one denied permission to emigrate.

The Vera and Donald Blinken Open Society Archives holds textual documents about commemorating the murdered Jewish poets in two archival series. The series Soviet Red Archives and Samizdat Archives were collected, cataloged, and analyzed by the Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (RFE/RL) Research Institute between 1949 and 1994. However, the main source about commemorative activities dedicated to the JAC is the audio collection of the RFE/RL Russian Broadcast Records. This collection, digitized and available online, contains unique audio files broadcast by the RFE/RL Russian Service between 1953 and 1995, spanning from the very first program on air till post-perestroika years. The broadcasts (news reports, interviews, literary readings, samizdat reviews, etc.) cover various aspects of the Soviet and émigré political, economic, social, and cultural life. This digitized audio collection was donated in 2014 to the Blinken OSA for processing, metadata enhancement, and online dissemination by the Hoover Institution Archives at Stanford University, California. Among over 10 thousand hours of recordings and 26,147 unique audio files, 26 programs spanning from 1972 to 1994 address the tragic fate of the JAC and its members, in the shows Special Programme, On the Events of the Day, Shalom, Culture, Fates, Time, and Jewish Cultural and Social Life.

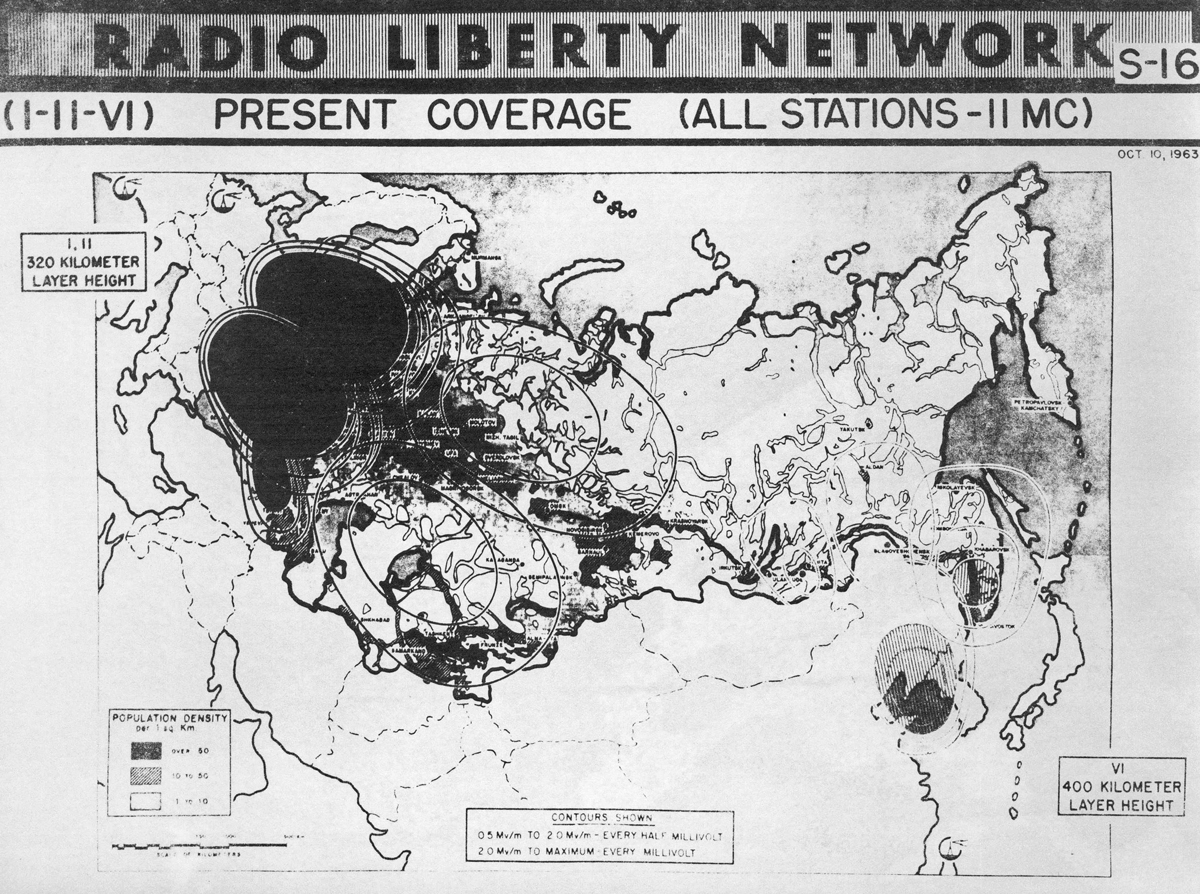

Map outlining Radio Liberty’s coverage in the USSR.

Map outlining Radio Liberty’s coverage in the USSR.

(HU OSA 300-1-8 RFE/RL Research Institute, Public Affairs Photographic Files)

In the 1970s, with an influx of Russian-speaking emigrants from the Soviet Union to the West, including famous poets and writers of Jewish descent, the RFE/RL Russian Service invited recent immigrants to join their staff. They not only had intimate knowledge about Soviet Jewish history and culture; Stalinist persecution had a special significance for those now producing radio programs. Reporting the present-day challenges of Jewish emigration from the Soviet Union, and the very reasons to emigrate, meant telling their own stories.

One of the most moving techniques these radio broadcasts used to tell the audience about the Committee, and especially about its perished literary and artistic members, was the thoughtful narration of their creative legacies. Experts gave details about how skillful and talented Solomon Mikhoels was as actor and artistic director of the Jewish theater. Celebrities, such as writer Ilya Ehrenburg or singer-songwriter Alexandr Galich, were interviewed for their memories of meeting the deceased or their family members. Radio Liberty even broadcast a 1940s recording of Mikhoels playing Tevye the Milkman in Yiddish, and excerpts of theater performances. Other original audio recordings included Perets Markish reading his poem Fragments (1943) in Yiddish, or another of his poem, Mikhoels (1948), translated into Russian and read by his son. These had two important functions. First, they claimed Soviet culture in Yiddish to be an essential part of not only the Soviet sphere, but also of global Jewish culture. Second, they targeted strong national and identity feelings. Recordings of Itsyk Fefer reading in Yiddish his poem On the River Bira (1937) about a failed project of Jewish autonomous region in the USSR, and especially his poem I am a Jew (1941), were essential for these matters. The radio broadcasts metaphorically stated that bullets cannot kill ideas or talents, and that art would eventually overcome violence.

Radio Liberty programs cited family members to reconstruct the trauma of the arrests (sound of the door closing behind Perets Markish for the last time, worrying about the personal archives of the arrested) and of the stigma of being a family member of “an enemy of the people.” Special emphasis was put on the personal responsibility of Joseph Stalin; the Soviet state was accounted for silencing the murder, for keeping the fate of the arrested JAC members secret, for not informing even the families about the verdict till Stalin died. In one of the shows, Ester Markish, widow of the murdered poet Perets Markish, recounted how she was notified about her husband’s rehabilitation in 1955. She was called to the state security facilities together with other wives of the defendants; without any information on their husbands, they still hoped that they were alive. Here they were told that the court had repealed the death sentences as there “was no substance to the charges”; which, nevertheless, could not ease the pain of losing their husbands.

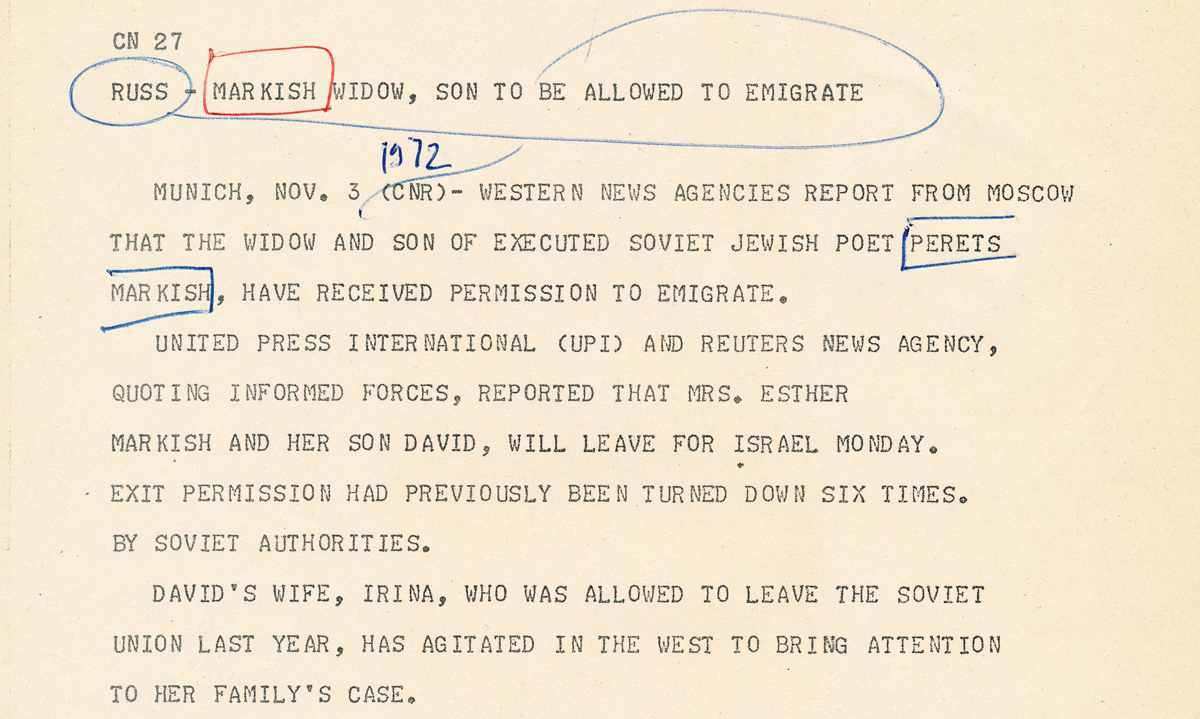

RFE/RL Central Newsroom release on Esther and Dovid Markish’s 7th, successful visa request.

(HU OSA 300-85-13 RFE/RL Research Institute, Samizdat Archive, Biographical Files)

The story of the family of the executed poet Perets Markish was an exemplary one. His wife Esther and son David were refused six times to get exit visas from the Soviet government, before finally emigrating to Israel in 1972. This was made possible to a larger extent due to a hunger strike David started, and to an international campaign led by Irina Markish, David’s wife, who was allowed to emigrate a year earlier, in 1971. In 1973, after leaving the Soviet Union, Esther Markish travelled to the West to join a campaign supporting Soviet Jews’ right to emigrate. Interviewed by RFE/RL, she stated that the freedom of movement was guaranteed by the Constitution of the USSR, and by making Jews stay, the USSR violated human rights. According to RFE/RL, 50,000 Jews arrived to Israel from the USSR by the early 1970s, and around 100,000 more were waiting for their exit visas. Many others were reluctant to request such visas, being afraid of the consequences, such as losing their jobs.

Last but not the least, the RFE/RL provided a platform for the children of the murdered members of JAC, actively involved in preserving their legacy in the 1970s and 1980s, to communicate their efforts to a larger public. Once in Israel, Dovid Markish continued his writing career and published his first novel, The Beginning, in 1976; an intimate autobiographical account that revived memories of his father, and dived into the peculiarities of postwar Jewish identity between loyalty to Socialism and Zionism. Dovid also translated his father’s poems from Yiddish into Russian, and helped publishing what he described as “the legacy of difficult fate.” The same was true of the daughters of Solomon Mikhoels, who emigrated to Israel in the 1970s; one of them, Natalia, wrote a memoir and read it on air on several occasions.

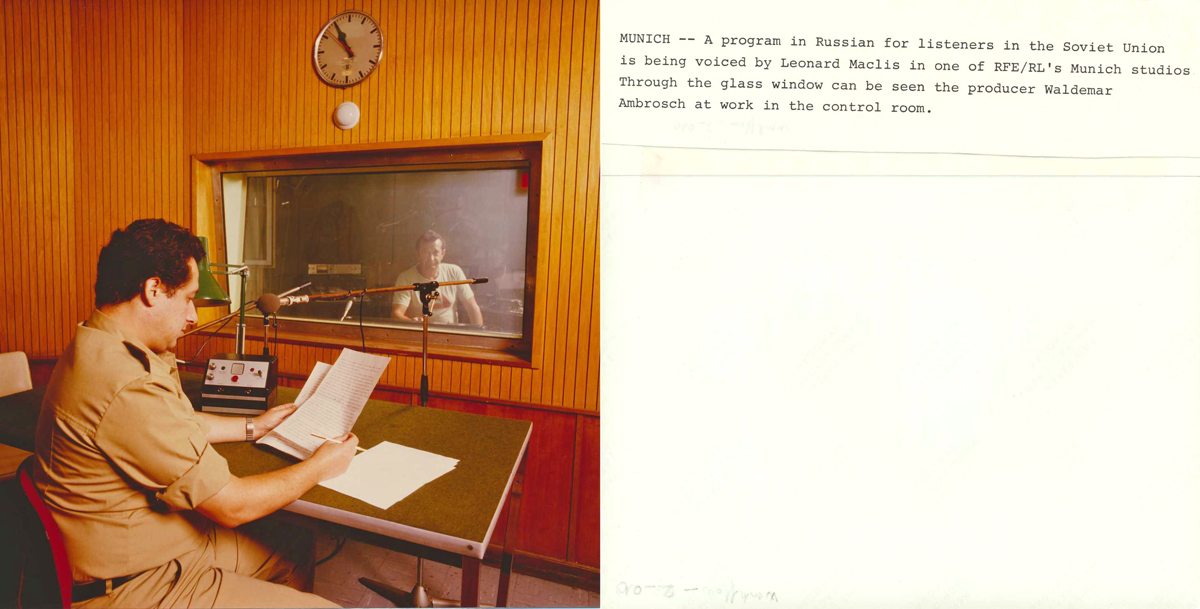

According to its original caption, this PR photo captures RFE/RL Russian Service host Leonard Maclis in the radio’s Munich studio.

According to its original caption, this PR photo captures RFE/RL Russian Service host Leonard Maclis in the radio’s Munich studio.

(HU OSA 300-1-8 RFE/RL Research Institute, Public Affairs Photographic Files)

In the 1970s and 1980s, Radio Liberty professionals adopted another important narrative trope; the complicated relations of Jews with the Soviet state, and especially the traumatic experience of persecution. The broadcasts reminded the audience that after the 1917 October Revolution, the Soviet state initially embraced the development of a politically loyal culture in Yiddish, sponsored Soviet Yiddish literature and performing arts, awarded state prizes to and during the war heavily relied on Jews—including the JAC. Thus, the targeted persecution of the Committee, the deportation of members’ families in 1952–1955, and the entire postwar anti-Semitic campaign, were interpreted as the Soviet state betraying its Jews. As a result, Jewish American organizations, such as the Congress for Jewish Culture, the Workmen’s Circle, or the Americal Jewish Commitee, came to discuss Soviet Yiddish culture “through the lens of the Purge,” i.e., as a victim of the murderous state. In the 1980s, the Radio Liberty interpreted the execution of the JAC members as a continuation of the Holocaust, and compared Stalin to Hitler in his urge to eliminate Jewish life in Europe and beyond. Although Stalin’s anti-Semitic campaign ended with his death in 1953, one year after the Night of the Murdered Poets, the persecution of Jews in the USSR continued. Broadcasts reported on the many challenges Soviet Jews were facing at home throughout the 1960s–1980s: various taxes (for instance in education) and criminal prosecution. The radio also covered the transnational agency in support of Soviet Jews: requests for amnesty, rallies in England, France, and the US, hunger strikes of those newly arrived at Israel protesting the imprisonment of Jews in the USSR, and so on.

All the above efforts of the authors and editors at RFE/RL, of recent emigrants, and of the intimate circle of the executed members of the JAC, significantly contributed to preserving the memory of the murdered poets’ lives and deaths. At the same time, they produced unique knowledge about Soviet Jewish culture in Yiddish, and mediated it both to the international audience and the one behind the Iron Curtain: a territory many Jews sought to leave, but nevertheless kept close ties to for several generations.