Vera and Donald Blinken Open Society Archives

From Coal Cellar to Domed Hall (and Beyond): 45 Years Since the Return of the Holy Crown

Matthew Nimetz, a Trustee of Central European University, told the following story on a cold winter’s day in Nádor Street: “In the late fall of 1977, when US President Jimmy Carter decided to return the crown of St. Stephen to Hungary, he instructed me, as his chief advisor to the Secretary of State, to travel to Fort Knox, Arizona, where the Hungarian crown jewels were stored along with the gold holdings of the US Federal Reserve Bank, and see the condition of the crown jewels. Opening the lid of the chest, kept in a safe behind the vault doors, revealed a shocking sight: the cross topping the crown was apparently crooked. I feared that when the Hungarians saw this undeniable consequence of carelessness, President’s generous gesture would lead to an unforeseeable diplomatic scandal. As I extended the thumb and forefinger of my right hand to undo the damage and straighten the bent cross in one motion, a staffer of the Washington National Gallery of Art accompanying me took my hand, warning: ‘Don’t do it! You'll end up breaking the cross, and more trouble will come of it. It’s better not to deny it.’ That's when we decided to invite Hungarian experts to inspect the crown jewels before the handover, to prevent such surprises in Hungary. On December 14, 1977, the delegation of Hungarian experts arrived at Fort Knox, and when the chest containing the crown jewels was opened, I saw tears in their eyes. I thought the shock was for the distorted cross, but it turned out to be tears of emotion.”

Matthew Nimetz, a Trustee of Central European University, told the following story on a cold winter’s day in Nádor Street: “In the late fall of 1977, when US President Jimmy Carter decided to return the crown of St. Stephen to Hungary, he instructed me, as his chief advisor to the Secretary of State, to travel to Fort Knox, Arizona, where the Hungarian crown jewels were stored along with the gold holdings of the US Federal Reserve Bank, and see the condition of the crown jewels. Opening the lid of the chest, kept in a safe behind the vault doors, revealed a shocking sight: the cross topping the crown was apparently crooked. I feared that when the Hungarians saw this undeniable consequence of carelessness, President’s generous gesture would lead to an unforeseeable diplomatic scandal. As I extended the thumb and forefinger of my right hand to undo the damage and straighten the bent cross in one motion, a staffer of the Washington National Gallery of Art accompanying me took my hand, warning: ‘Don’t do it! You'll end up breaking the cross, and more trouble will come of it. It’s better not to deny it.’ That's when we decided to invite Hungarian experts to inspect the crown jewels before the handover, to prevent such surprises in Hungary. On December 14, 1977, the delegation of Hungarian experts arrived at Fort Knox, and when the chest containing the crown jewels was opened, I saw tears in their eyes. I thought the shock was for the distorted cross, but it turned out to be tears of emotion.”

President Carter’s decision was announced in the American press on a very ill-timed day, on November 4, 1977; just 33 years after ultranationalist Ferenc Szálasi took his presidential oath on to the crown, and 21 years after Soviet troops entered Budapest to crush the Hungarian Revolution of 1956.

The Holy Crown and the coronation jewels on view in the Ballroom of the Royal Palace, 1938

The Holy Crown and the coronation jewels on view in the Ballroom of the Royal Palace, 1938

( Fortepan/Zsolt Pálinkás)

The crown of the kingdom without a king was hidden from the advancing Red Army multiple times in the last months of World War II: first in the coal cellar of the Crown Guard building, from where it was smuggled back on the orders of Ernő Pajtás, the commander of the Crown Guard, who was on good terms with Szálasi, so that the Arrow Cross leader could legitimize his coup d’état by swearing an oath on the crown. (Pajtás was promoted to the posthumous rank of Major General by the President of the Republic in 1992 on the recommendation of the Minister of Defence.) Next, the crown jewels and the royal robe were finally smuggled into Austrian territory by Szálasi on March 28, 1945, only to find refuge, in the end, in a halved, buried gas barrel, until, in July 1945, they fell into the hands of the occupying American troops.

The US never regarded the regalia as spoils of war; they were placed in the custody of the Monuments, Fine Arts & Archives Administration—along with artifacts stolen by the Nazis, including a painted bust of Nefertiti, wife of Pharaoh Akhenaten—and transported to Fort Knox in 1953. Because of the political uncertainty after the war, the Americans refused to return the crown before the signing of the Paris Peace Treaty; and later they kept hold it at the request of Prime Minister Ferenc Nagy, who emigrated to the States after having been overthrown by the Communists. The Communist takeover, the beginning and escalation of the Cold War, and the lawsuits against Hungarian church leaders (Archbishop Mindszenty of Esztergom among them) did not create a favorable climate for the return of the crown. In 1950, Mátyás Rákosi tried to get the coronation insignia back in exchange for the release of Robert Vogeler, who had been sentenced to 15 years in prison (Vogeler, executive of the American-owned Standard Electric Co., had been convicted in a so-called economic show trial allowing the Communists to take state ownership of the plant.)

Edith Standen and Patrick J. Kelleher, Monuments, Fine Arts & Archives Administration experts with the regalia, 1946. Kelleher, art historian at Princeton University, wrote his doctoral thesis on the Holy Crown, he published his research in 1951. Kelleher also accompanied the Hungarian experts identifying the insignia in 1977.

( Wikimedia Commons)

The Hungarian Revolution of 1956, the subsequent repression, Mindszenty’s forced voluntary exile in the US Embassy on Liberty Square (which inspired Woody Allen in 1965 to write the moderately successful comedy Don't Drink the Water), and the permanently tense world situation—often threatening with nuclear war—did not help change the American decision until the mid-1970s. The Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe was launched in 1973 (with US participation), and concluded on August 1, 1975, with the signing of the Helsinki Final Act; with their signatures, the parties effectively recognized the postwar status quo in Europe. The West expected the Final Act to result in somewhat freer dialog and more meaningful cultural contacts across the Iron Curtain, and in greater protection of human rights in Eastern Europe. In contrast, the USSR saw the document as a confirmation of their sphere of influence; at the same time, the first Eastern European human rights organizations emerged as an unintentional effect of the Final Act. The foreign policy of Jimmy Carter, a deeply religious, devout Baptist, regarded the support of human rights movements a moral principle as crucial as the thaw between the two world orders, the latter pursued by gestures to Eastern European regimes. It was in this context that the possible return of the Hungarian crown was raised again.

Seeking consolidation after 1956, Hungary reached a partial agreement with the Vatican in 1964, in an undisclosed part of which the Pope agreed not to appoint bishops to Hungary without the consent of the Hungarian state; thus the Catholic hierarchy was headed by “peace priests” collaborating with the authorities. As result of a 1971 agreement, Mindszenty left the US Embassy in Budapest for Rome as a sign of his obedience to the Pope. In the summer of 1977, Pope Paul VI received János Kádár and his wife—even presented her with a rosary—and was visited that same year by Walter Mondale, Carter’s vice-president. Presumably, the case of the Hungarian crown was discussed at both meetings. Carter, however, also had to convince a very skeptical American public, which included a considerable number of Eastern European émigrés who had arrived at the United States mostly after World War II and the 1956 Revolution. As part of a campaign serving this purpose, two archbishops of the American Catholic Church, Arthur Schneier, the Hungarian-speaking Chief Rabbi of New York who had been in hiding in Budapest during World War II, and the influential Baptist preacher Billy Graham, a close friend of Carter, were sent to Budapest. The Hungarian Baptist Church believes that it was thanks to Hungarian Baptist influence that the Baptist preacher convinced the Baptist US President of the importance of returning the Holy Crown.

Matthew Nimetz, mentioned at the beginning of the story, argued before the US House Foreign Affairs Committee that the crown’s return would have a positive effect on the national consciousness of Hungarians, and would make the Communist regime more tolerant of religious groups and more friendly toward the United States. When he suggested that Hungarians were able to travel more freely to the West than other citizens of Eastern Europe, the Hungarian émigrés present expressed their disapproval with derisive laughter; while the proposed resolution by Representative Mary Rose Oaker of Ohio—who also represented an extensive Hungarian community—to make the return of the crown conditional on the complete withdrawal of Soviet troops from Hungary, was greeted with enthusiastic ovations. Someone hoped that the red star topping the Hungarian Parliament building would be replaced by a crown; another congressman, however, compared the repatriation of the crown to the Chief Rabbi of Warsaw presenting Adolf Hitler with a precious Torah Roll in 1941 for his special treatment of the Jews. Former Prime Minister Ferenc Nagy, who was present, explained in a long speech why, contrary to his convictions 30 years earlier, he now supported the repatriation of the crown, along with Béla Király, former commander-in-chief of the 1956 National Guard.

Housing the Holy Crown until 1978, Fort Knox in 1968.

(Wikimedia Commons)

In the end, dissenters were unable to overturn the president’s intentions either with legal arguments or court actions, but the debates did not end with the decision. A letter published in the Washington Star argued that Slovaks, Croats, Romanians, and Ruthenians also lived under the Holy Crown, and that the crown should be theirs as well. Besides, only five of the Hungarian kings spoke the Hungarian language. The best solution would be to auction the crown and “distribute the profit to the relatives of the 800,000 Magyar Jews who were murdered by the Nazis and Magyar fascists during World War II.” The Katolikus Magyarok Vasárnapja (Catholic Hungarians’ Sunday) wrote: “Others, in their final despair, wished that the plane carrying the Holy Crown crashed, that the most sacred Hungarian relic be destroyed rather than to fall into the hands of godless Bolsheviks.” The author ended his writing with a quote from the Gospel of Matthew: “do not cast your pearls before swine.”

After repeated postponements, the ceremonial presentation of the crown in Budapest was finally scheduled for January 6, 1978, the day of the Epiphany. The coronation jewels had arrived at Ferihegy the previous night on Air Force Two, at an unannounced time. The crown was accompanied by a delegation of US politicians (including the aforementioned Nimetz), churchmen, and Hungarian-Americans, including Theodore Weiss, the only member of the US House of Representatives of Hungarian descent, István Deák, a historian at Columbia University, and Albert Szent-Györgyi. The delegation was led by the US Secretary of State, who handed the crown over to Antal Apró, Speaker of the Hungarian Parliament.

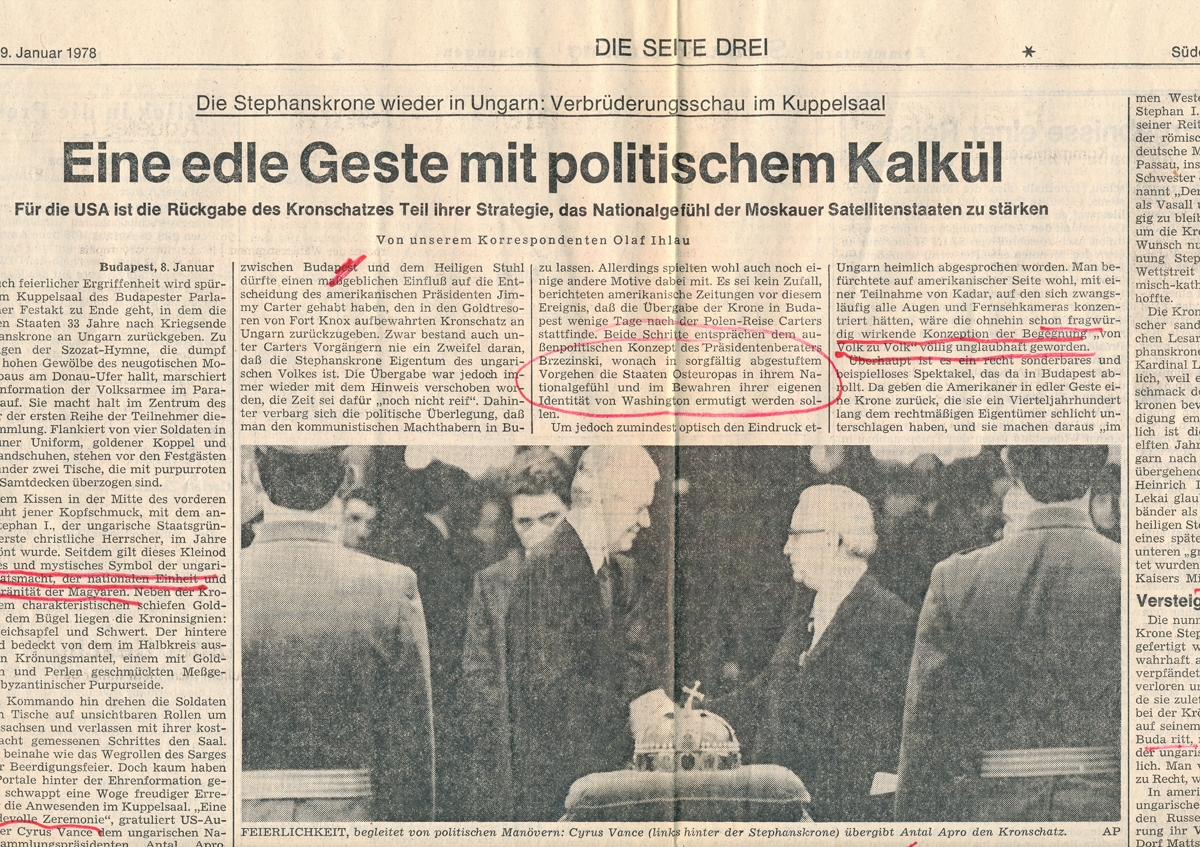

In his report A Noble Gesture with Political Calculation, Süddeutsche Zeitung correspondent Olaf Ihlau suggested that “returning the crown is part of the US strategy to strengthen national feelings in Moscow’s satellite states.”

(HU OSA 300-40-1 Records of RFE/RL Research Institute, Hungarian Unit, Subject Files)

The ceremony—broadcast by state television with a two-hour delay to allow the cutting out of potential unpleasant remarks in the US Secretary of State’s speech—was attended by a carefully selected group of Hungarian personalities, including Ignác Pióker, the famous Stakhanovist, along with politicians, peace priests, workers, and peasants, as well as poet Gyula Illyés, writers Anna Jókai and Magda Szabó, pianist Zoltán Kocsis, opera singer Sylvia Sass, cinematographer Sándor Sára, actress Éva Ruttkai, anatomist János Szentágothai, and the editor-in-chief of the weekly Nők Lapja (Women’s paper). The Hungarian government has even allowed Radio Free Europe correspondent Tom Bodin to set foot in the country and cover the ceremony.

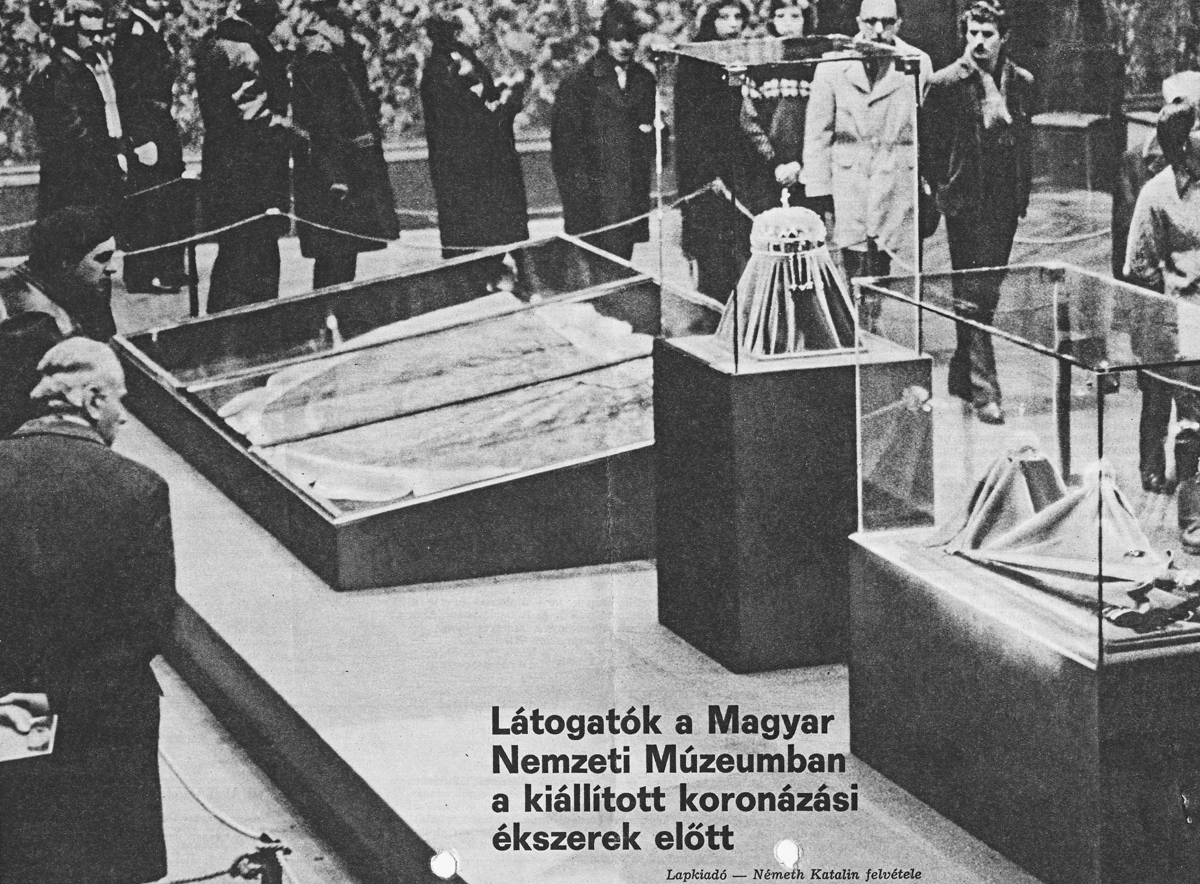

On the night after the ceremony, the chest containing the regalia, secured with several keys and seals, was transported to the Hungarian National Museum’s storage for Scythian, Longobard, Avar, and Germanic gold treasures. The US insisted that the crown be put on public display. György Aczél, the party’s chief censor of culture at the time, had allegedly intended to install it in the director’s office in the Hungarian National Gallery; the decision however was to exhibit it in the ceremonial hall of the National Museum. The Holy Crown’s ordeal did not end there, however.

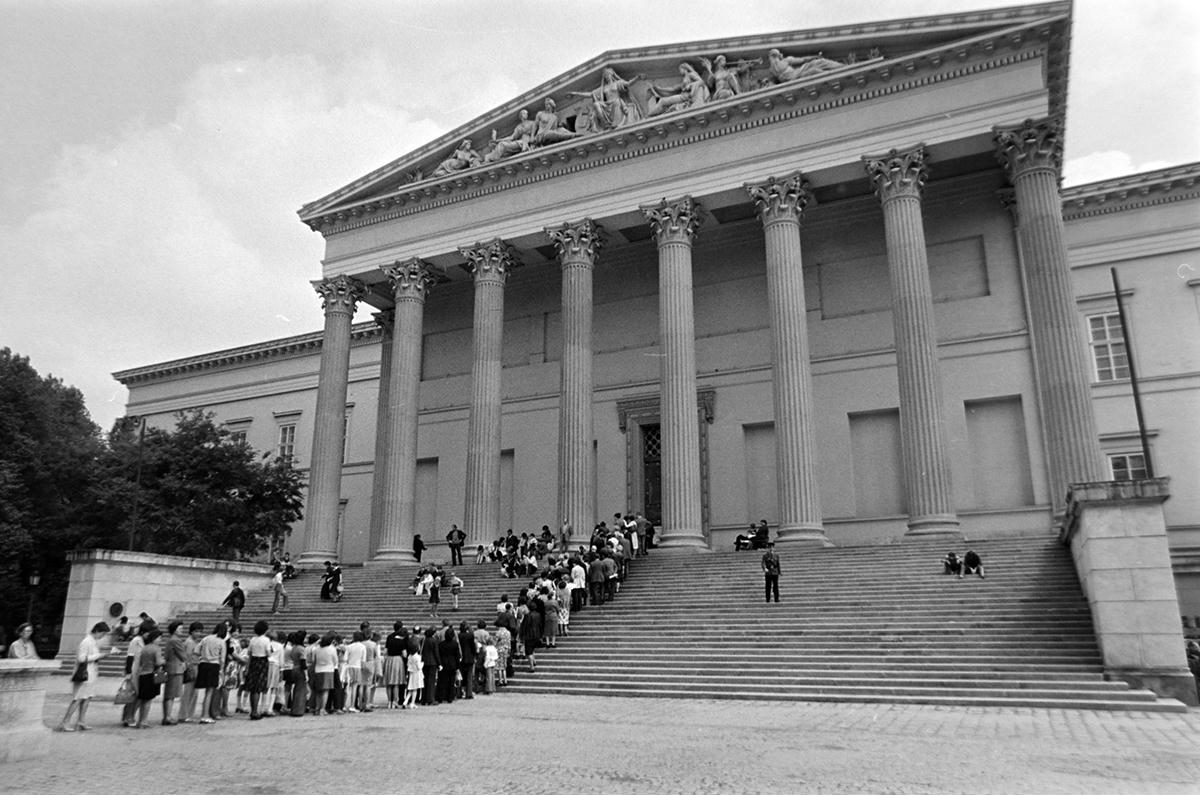

Visitors arriving at the Hungarian National Museum to view the Holy Crown, 1978

(Fortepan/Viktor Gábor)

At the tripartite negotiations preceding the regime change in 1989, the issue of a new coat of arms for the republic was also on the agenda, along with a complete reform to the current constitution. The overwhelming majority of the opposition opted for the so-called Kossuth Coat of Arms, lacking the crown. As József Antall put it, “you must realize that we . . . have enforced an almost totally new constitution. . . . Almost not a single character remained, really. And then the coat of arms of the People’s Republic should stay? . . . Society will be misled by the question of the coat of arms. It is a manipulation, along with the crowned coat of arms.” Antall foresaw the future. Soon thereafter, Kálmán Kulcsár, a former military prosecutor and sociologist, Minister of Justice in the Grósz and Németh governments, raised the idea of “a heraldically more authentic,” so-called crowned coat of arms. Two alternatives were put before the newly-elected National Assembly: the Kossuth Coat of Arms, embodying the democratic-revolutionary, popular tradition of 1848 and 1956, argued for by historian György Szabad, Speaker of the National Assembly, and Béla Király, the commander-in-chief of the 1956 National Guard, among others; and the crowned coat of arms, symbolizing the thousand-year statehood, supported by General Kálmán Kéri, historian Tamás Katona, and others. After a long historical and ideological—and often personal—debate, a qualified majority voted in favor of the crowned version.

In 1996, the Parliament still rejected Dr. Ágnes G. Nagy’s proposal on the “Custody and Care of the Holy Crown,” according to which the Holy Crown would have been transferred from the Hungarian National Museum to the Parliament building. Just three years later, however, as the so-called “Hungarian Millennium” approached, the Fidesz government submitted to Parliament the text of Act I of 2000 on the “Commemoration of the Founding of the State of St. Stephen and the Holy Crown,” which enshrined in law the visionary ability of St. Stephen, his sense of mission, his trust in divine providence, his iron will, and the fact that Christianity had made it possible for “the Hungarian nation to repel the attacks on its existence.” Although the original version of the text stated that “the Holy Crown remains to embody the unity of the Hungarian state,” the law, to the protests of the opposition, finally declared, as a “compromise,” that “the Holy Crown lives on in the nation’s consciousness and in the Hungarian public tradition as a relic embodying the continuity and independence of the Hungarian state.” (In April 2011, with no pressure to consider the opposition’s arguments anymore that the source of power in a democracy can only be the people and not the Holy Crown, the preamble of the new constitution—abolishing its republican predecessor—reverted to the original version of the text: “We honour the achievements of our historic constitution and we honour the Holy Crown, which embodies the constitutional continuity of Hungary’s statehood and the unity of the nation.”)

“Visitors in front of the coronation jewels in the Hungarian National Museum,” 1978

(HU OSA 300-40-1 Records of RFE/RL Research Institute, Hungarian Unit, Subject Files)

In the debate of the law on St. Stephen and the Holy Crown, Minister of Justice Ibolya Dávid recalled the circumstances of the crown’s repatriation: “The placement of the Holy Crown in the Domed Hall of the Parliament will symbolize that the National Assembly—as the embodiment of the Hungarian Republic’s sovereignty—pays respect to the historical symbol of Hungarian statehood, the Holy Crown. On January 6, 1978, Secretary of State Cyrus Vance, representing and on behalf of the people of the United States, presented the Coronation insignia to the Hungarian people in the most fitting place, the Hungarian Parliament building.” The law provided that the “Holy Crown and its accompanying insignia, with the exception of the coronation robe, shall be kept in the Parliament building.” The historian Miklós Szabó, a former lecturer of the pre-1989 illegal university course of the democratic opposition, and a former MP of the Alliance of Free Democrats – Hungarian Liberal Party, said of the decision: “The crown will be moved to the Parliament or—according to the latest idea—to the Castle. In fact, the current coalition would sacrifice the republic on the altar of an imaginary monarchy. As a result of these measures toward refeudalization, Hungary is to become a semi-operetta country. . . . Just semi, as it won’t be pleasant, but ridiculous.”

On January 1, 2000, the crown was carried to the Parliament building on a royal-blue vehicle, to the sound of a 21-gun salute. At the main gate, the regalia were received by the recently-established Crown Council, the President of Hungary, the Prime Minister, the Speaker of the House, the President of the Constitutional Court, and the President of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. In his ceremonial speech, the Prime Minister expressed his conviction that while a man without bread, without shelter, without warmth is still a man, without his past and traditions he is certainly not. The Holy Crown, the orb, the sceptre, and the sword were placed in a special vault in the Domed Hall of the Parliament. It would have been a shame to let this uplifting opportunity go unused and not to see the potential in it. The cost of fitting the crown in its proper place was estimated at 150 million forints. The allegedly earthquake-proof display case for the crown, filled with nitrogen instead of oxygen, was supplied by CCC+Bogner, a company owned by Karl Dieter von Bogner and the Bogner+Lord Cultural Consulting (based in Vienna, London, Toronto, Szentendre, and at Üllői Street 34 in Budapest). One of the two Hungarian chief executives of the firm was called Koppány Varga, the other, whose political and financial rise began here, Árpád Habony. Only these white-gloved so-called crown guards could touch the crown. Built at a cost of 28 million forints and set up with 15 million forints worth of security equipment, the crown and the coronation jewels are said to be shielded from natural light and, because of the special lighting, they are never in shadow, as is right.

The Holy Crown on view in the Parliament building, 2010

(Wikimedia Commons)

After the 2010 general elections, when the cultural and scientific institutions were evicted from the Castle and the Royal Palace—their location since 1956—and the transformation of the area for representational purposes began, the question of whether the Palace would be the most suitable place to keep the crown was naturally raised again. As former Prime Minister Péter Boross noted in 2019, “in the Domed Hall of the Parliament, the Holy Crown does not receive the respect that has, throughout the centuries, been engraved in generations... The crown would require a more dignified location. It is disturbing that anyone can go to the Holy Crown, tourists can visit it in inappropriate attire, in a pair of trousers, and young women can visit it in skimpy clothes with bare breasts.”

In his article A Szent Korona népe (People of the Holy Crown), Ottó Habsburg wrote, “Nowhere in Europe is there anything like our (sic!) old constitution. It gives us endurance and inner equilibrium, which is our great strength in difficult times. For the Holy Crown—and only a Hungarian (sic!) understands this—has always been the center of our constitutional life. According to the true doctrine of the Holy Crown, the head of the Hungarian state is not a person, but the sanctity of the nation, the crown.”