Vera and Donald Blinken Open Society Archives

Remembering Andrei Sakharov: The Truth of One Man

”Westerners ask how Soviet citizens feel about their government's actions in Afghanistan; this question is difficult to answer in the absence of a free press and without public opinion polling on sensitive issues. On the surface, at least, there seems to be astonishing indifference to the true nature of events in Afghanistan, where our sons have become murderers and oppressors—and victims—of a terrible, cruel, dehumanizing war.” – Andrei Sakharov on the war in Afghanistan in his book Memoirs

On December 14, 1989, Andrei Sakharov died in Moscow. A symbol of the historic changes in the Soviet Union in the late 1980s, Sakharov played a crucial role in educating the general public on the fundamental importance of democratic values. His life is unique and paradoxical—an outstanding physicist known for his role in the creation of the hydrogen bomb, and at the same time, a zealous civil rights advocate, the first Soviet citizen to be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

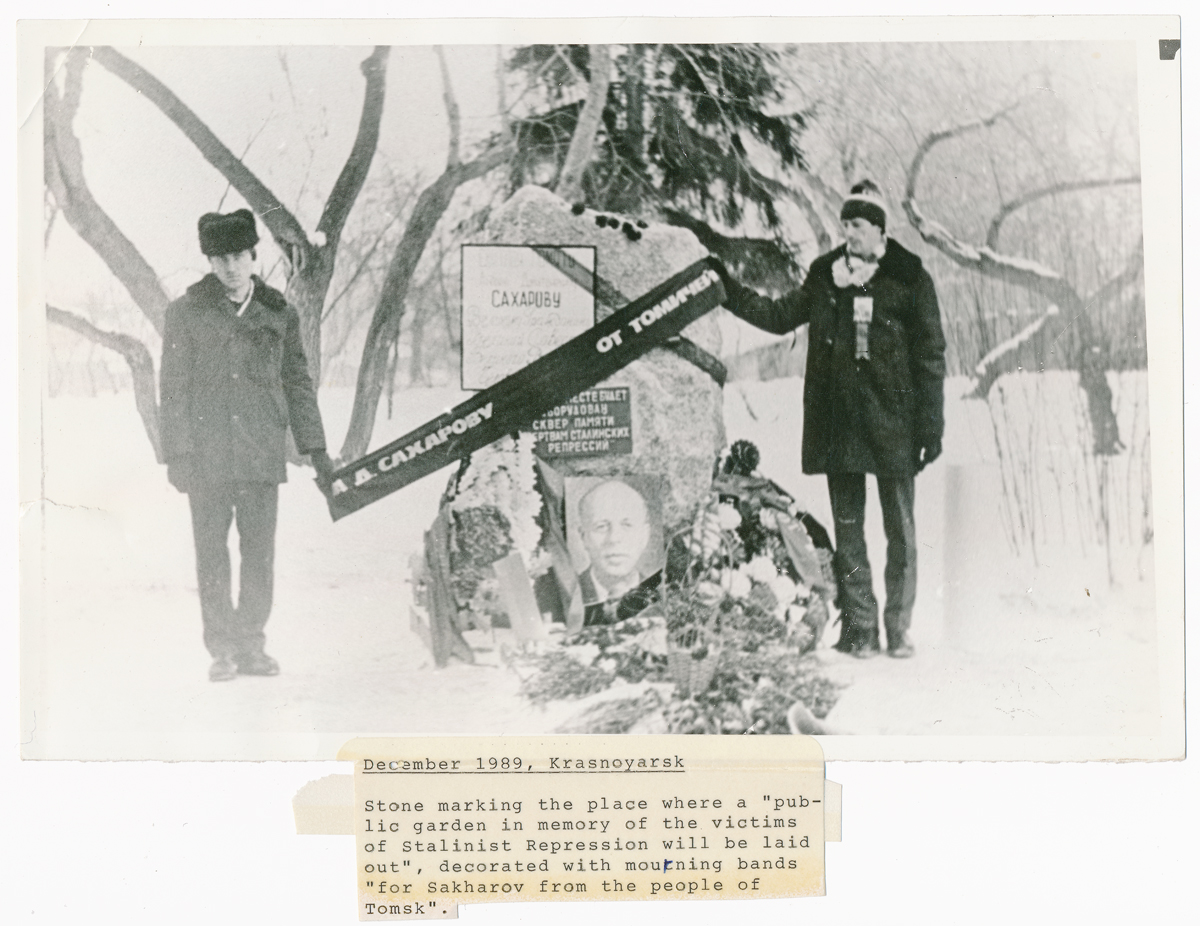

Photograph received by Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, and preserved at Blinken OSA.

Photograph received by Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, and preserved at Blinken OSA.

(HU OSA 300-85 Records of RFE/RL Research Institute, Samizdat Archives)

The Vera and Donald Blinken Open Society Archives preserves various records that document the most important events of Andrei Sakharov’s final years, which he fully devoted, as chairman of Memorial Society to the memory of the Soviet state terror’s victims on the one hand, and as opposition leader at the Congress of People’s Deputies of the Soviet Union to the struggle of democratic reforms on the other. As it often happens, his homeland came to grasp Sakharov’s significance in shaping the Russian society only after his death.

When Mikhail Gorbachev took office in 1985, the world-famous academician was in exile. Sakharov was arrested in 1980, stripped of all state awards (of which he had many), and without trial, was sent into exile to Gorky (now Nizhny Novgorod) together with his wife, Elena Bonner. The general understanding was that the cause for the punishment was Sakharov’s open criticism of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, and his repeated calls to the international community to condemn the actions of the USSR. In exile, Sakharov held and survived three hunger-strikes, many months of hospitalization, force-feeding, and the round-the-clock surveillance by the KGB. With Bonner, they lived in strict isolation, deprived of any communication with the outside world; until, in December 1986, KGB officers unexpectedly visited them in their flat in Gorky, and installed a telephone. The next day, they received a personal call from Mikhail Gorbachev, who told them they could return to Moscow. Sakharov was not caught off-guard, and demanded Gorbachev to release all political prisoners; which Gorbachev did, signing the respective decree a year later. This event symbolically marked the beginning of the perestroika (restructuring) era.

After returning to Moscow, Sakharov plunged into the political work, becoming one of the driving forces for advocating reforms. He made several landmark visits abroad, where he met with Ronald Reagan, Margaret Thatcher, Francois Mitterrand, and even Pope John Paul II. His writings and interviews appeared in many magazines worldwide. The last year of Sakharov’s life, 1989, saw critical historical events in the USSR—including the first partially free elections of the Congress of People’s Deputies of the Soviet Union, and the withdrawal of the Soviet troops from Afghanistan. For Sakharov personally, it was an extremely stressful and exhausting year. In March 1989, he was elected a USSR People’s Deputy, nominated by the Academy of Sciences. (Originally, his candidacy was put forward by the electoral group of the Memorial movement.) From May 25 until June 9, 1989, the Congress of People’s Deputies of the Soviet Union had its first session in the Kremlin Palace of Congresses. At the Congress, Sakharov, as co-leader of the opposition faction Inter-Regional Deputies Group (IRDG), issued numerous fundamental statements and delivered several speeches.

Andrei Sakharov Speaking at Day 1 of Congress of People’s Deputies of the Soviet Union, May 25, 1989. Expressing “hope that the Congress will prove worthy of the great mission that lies before it, that it will democratically approach the tasks before it,” Sakharov urged the Congress of People’s Deputies of the Soviet Union on its first day to discuss its course of action first, before voting on laws. Already this first speech was interrupted and followed by shouts.

Excerpt from the full recording.

(HU OSA 300-81-9 Records of RFE/RL Research Institute, Video Recordings of Soviet and Russian Television Programs)

Eventually, deputies took to expressing their irritation, and some of Sakharov’s talks were accompanied by shouts and whistling from the audience. When Sakharov was repeatedly booed by agitated deputies, Yuri Afanasiev, a historian and co-chair of IRDG, called those deputies “an aggressively obedient majority.” This phrase became a defining term in the struggle for democratic reforms. When on June 9, the closing day of the Congress, Sakharov introduced his Decree on Power, deputies refused to give him platform; yet Gorbachev, who chaired the session, insisted on allowing Sakharov five minutes to speak.

It was probably the most important event of the Congress. Sakharov appealed for removing Article 6 of the USSR Constitution, which established the monopoly of the Communist Party. He was determent to announce his proposal in spite of the limited time he was given. He kept reading, “Urgent measures are required to deal with the current situation of acute interethnic tensions. I propose the creation of a new constitutional system based on horizontal federalism.” He demanded that the top officials of the USSR should be elected by and accountable to the Congress, the KGB’s activities should be limited to foreign threats, and the size of the Soviet army should be reduced. Mikhail Gorbachev interrupted him, saying “Time’s up. Don’t you respect the Congress?” Sakharov replied, “Yes, but I respect the country and the people more. My mandate extends beyond the bounds of this Congress.” At this point, Gorbachev switched Sakharov’s microphone off.

The content of Sakharov’s interrupted speech became the crescendo of perestroika, and illustrated the titanic shift in the political rhetoric of those years. The next day, June 10, 1989, at a mass rally in Moscow, Sakharov read out the full version of his speech. The text was published in several printed media.

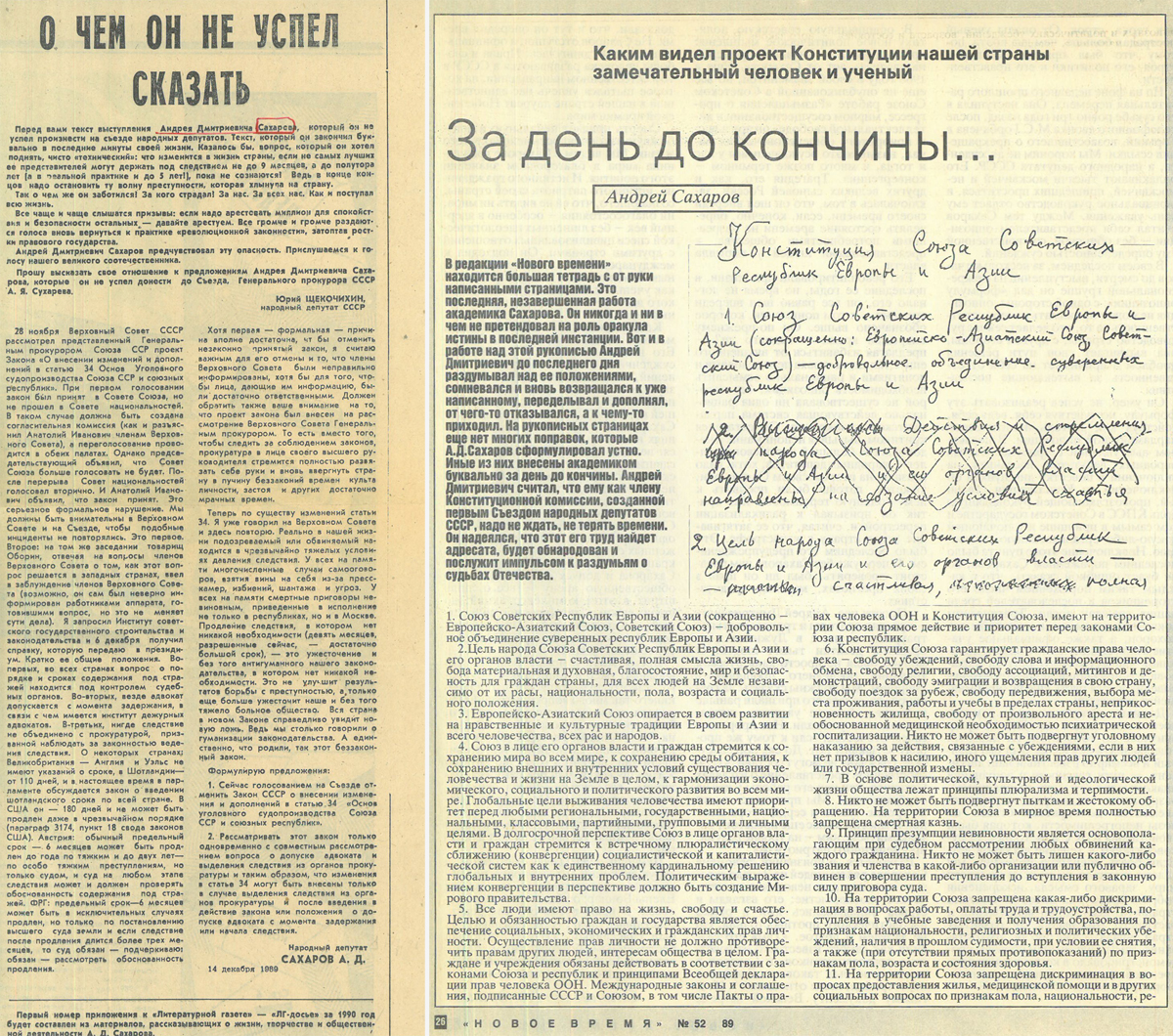

Sakharov's speech planned for the December 15 session of Congress, published in Literaturnaya Gazeta (l), and his draft constitution (with handwritten notes), published in Novoye Vremya (r).

Sakharov's speech planned for the December 15 session of Congress, published in Literaturnaya Gazeta (l), and his draft constitution (with handwritten notes), published in Novoye Vremya (r).

(HU OSA 300-80-7 Records of RFE/RL Research Institute, Soviet Red Archives, USSR Biographical Files)

After completing his work on the draft of the new Constitution in November 1989, Sakharov gave the Constitution of the Union of Soviet Republics of Europe and Asia to Mikhail Gorbachev. A significant part of the Sakharov Constitution was devoted to the protection of human rights and civil liberties; some contemporaries called the project utopian and even naïve. Nevertheless, Sakharov’s ideas had a strong impact on many political initiatives undertaken in the final years of the USSR. Partly, the draft of the New Union Treaty, initiated by Gorbachev in the hope of preventing the collapse of the USSR, took some of its ideas from Sakharov’s Constitution. However, with the failure of this new agreement (not independently of Ukraine’s people demanding independence) and the August 1991 coup d’état attempt, the dissolution of the USSR became irreversible.

Sakharov placed much hope in the Second Congress of People’s Deputies (December 1989). For the previous six months, activists of Memorial collected signatures supporting his Decree of Power; shortly before the start of the Congress, Sakharov was handed lists with hundreds of thousands signatures. On December 14, at a meeting of the IRDG, he encouraged his fellow deputies to organize a warning strike demanding Congress to immediately abolish Article 6 of the Constitution. On the evening of that day, Sakharov passed away.

People queuing to pay their last respects to Sakharov on December 17, 1989. Photograph received by Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, and preserved at Blinken OSA.

People queuing to pay their last respects to Sakharov on December 17, 1989. Photograph received by Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, and preserved at Blinken OSA.

(HU OSA 300-85 Records of RFE/RL Research Institute, Samizdat Archives)

On December 15, Sakharov was supposed to speak at the Second Congress of People’s Deputies; he had his speech ready. This text did not concern Article 6 of the Constitution, it was about something else. And this nuance illustrates well the scale of his personality, breadth of views, and remarkable capacities. Sakharov planned to talk about Article 34 of the Criminal Code, which defined the procedure, terms, and conditions of the detention of accused persons.

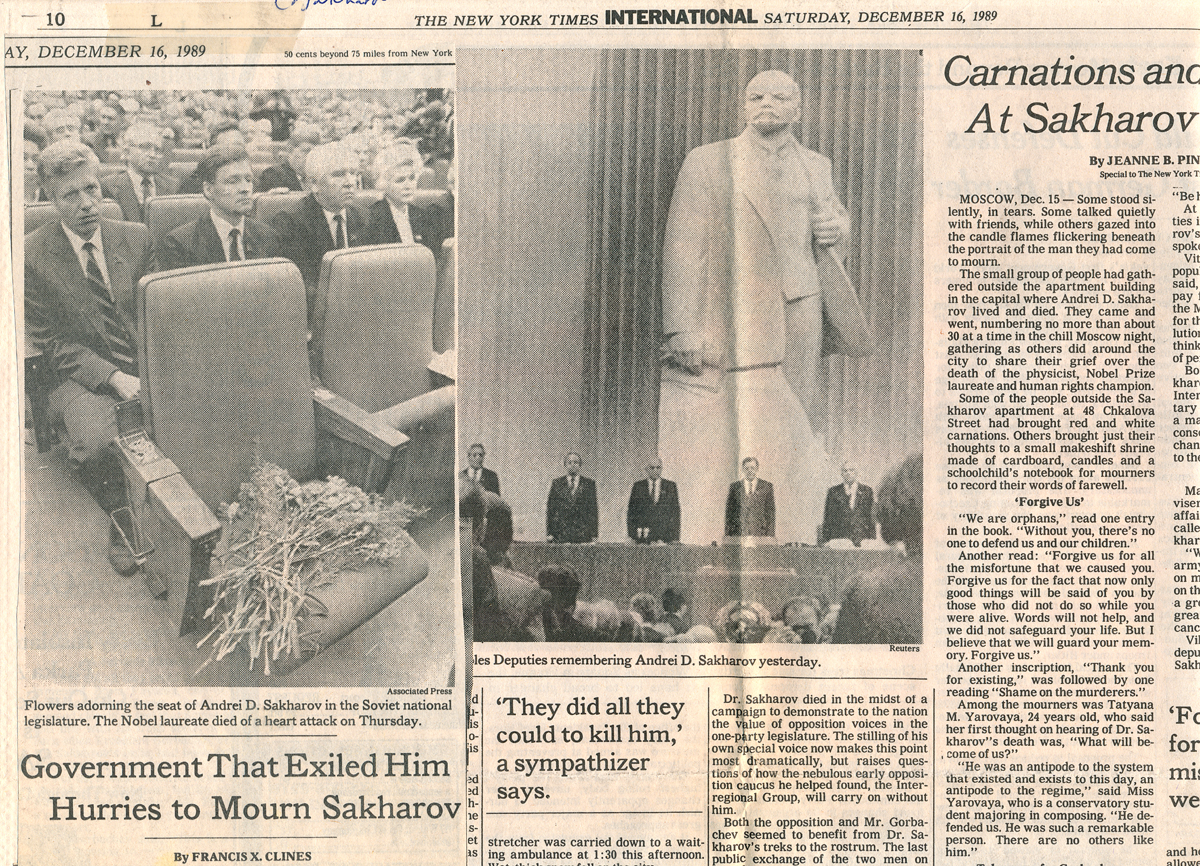

During the following days, front-page headlines across the Soviet Union and the whole world were devoted to Andrei Sakharov. Personal condolences were expressed by Thatcher, Mitterrand, Bush, John Paul II, and others. The funeral lasted two days. This event became a vivid evidence of the changes both in the political life of the country and in the minds of people. The funeral procession stretched for many kilometers on the streets of Moscow. The ceremony ended with a mass rally in Luzhniki.

Article 6 of the Constitution, declaring the leading role of CPSU, was abolished three months after Sakharov’s death; and the Soviet state itself survived him only by two years. In Congress, Sakharov’s deputy chair remained empty for the remaining days. In a sense, this chair would never be occupied. A figure with comparable degree of authority and scale like Sakharov has not appeared on the Russian political and public scene ever since.

The New York Times report on the Congress of People’s Deputies of the Soviet Union commemorating Sakharov, with his empty chair (l) and, among others, Gorbachev (r).

The New York Times report on the Congress of People’s Deputies of the Soviet Union commemorating Sakharov, with his empty chair (l) and, among others, Gorbachev (r).

(HU OSA 300-120-7 Records of RFE/RL Research Institute, Western Press Archives, Biographical Files)

The major issues raised by Andrei Sakharov were respect for human rights and civil liberties, national self-determination, state borders, nuclear disarmament, and the guaranty of peace. Today, it appears that Sakharov’s ideas had not been heard in his homeland. Sadly, the time when a citizen could openly criticize authorities from the podium of the Congress turned out to be painfully short, as much as the time of free elections, freedom of speech, and constructive political dialog. The path that today’s Russia has chosen is as far from the ideas and ideals of Sakharov as possible; but also of his opponent, Gorbachev, who passed away this August. Two Nobel laureates, two great contemporaries, two historical figures so different from each other, who had very different views of the country’s fate, but in the same direction; the direction of peace and change. Andrei Sakharov—who hurried Gorbachev with perestroika, and demanded an accelerated transition to democracy—did not live to see the USSR’s fundamental political transformation and eventual collapse. Mikhail Gorbachev, on the contrary, was witness to all the political and social changes in the country that he had provided with the freedom to choose its own way; and was witness to the most tragic events in post-Soviet history, leading to the current war against Ukraine.