Vera and Donald Blinken Open Society Archives

Should Facts of the Past Be Public?

The Blinken OSA launches a blog series at 444.hu, one of the leading independent news websites in Hungary. The blog entitled Forrás. [meaning source and, with the dot pronounced, boiling point] will consist of posts written by the Blinken OSA staff, revolved around archival documents and their archival, historical, and contemporary context. As 444.hu is in Hungarian, English translations will be published here, at the Blinken OSA website. In his introductory post, Blinken OSA Director István Rév addresses the trust in facts and in the preservers of facts, and discusses archives' complex relationship with open accessibilty and private information.

(Photo: Dániel Végel / Blinken OSA)

(Photo: Dániel Végel / Blinken OSA)

On December 1, 2001, fifteen scholars and activists met in Budapest, Hungary, in the Vera and Donald Blinken Open Society Archives (Blinken OSA), to establish the Budapest Open Access Initiative, making mostly publicly funded research results and millions of scientific publications unrestrictedly and freely available. The few monopolies dominating the industry of academic book and journal publishing, Elsevier, Springer, and Wiley, are responsible for approximately 42% of scientific articles. The Dutch Elsevier annually releases five hundred thousand academic papers in its twenty-five hundred journals, achieving an operating-profit margin of 36%; the company’s archive stores twenty million scholarly articles. In 2012, the digital academic library JSTORE responded to us that making the twelve million papers representing seventy-five scientific fields in its archive openly accessible would cost 250 million dollars.

Last year, Stanford University paid more than six million dollars for journal subscriptions, while countries affected by malaria barely have institutions with sufficient funds to subscribe to journals addressing malaria. Especially with regard to medical sciences, the difficulty of accessing the most recent research results (an annual subscription to Elsevier’s Brain Research is 11,522 dollars) is a matter of life and death.

Since the Open Access Initiative, the situation has changed. Leading public and private research funders, like the World Health Organization, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the European Commission, the Wellcome Trust, and most major universities, require the results of usually publicly funded research to be made open-access. In 2019, 31% of scholarly journals and 52% of scientific articles were open-access. Based on these trends, 72% of scientific articles may become open-access by 2025.

Boxes in the Blinken OSA repository.

Boxes in the Blinken OSA repository.

(Photo: Dániel Végel / Blinken OSA)

As far as common belief is concerned, the public has a right to access public information, as well as private information related to its community’s life or past, unless making such information public would violate state secrecy or the personal or private rights of individuals or private companies. Today, access to public information is often considered a basic human right. In 2001, we were naive enough to believe that soon we could simply make archival documents public. We were wrong.

Information that used to be strictly private not long ago, like sexual orientation, is in many places made public, while an individual’s sex, which was an accessible information in every civil register even in the recent past, in some countries is now a personal matter. The state police documents of past oppressive regimes often include sensitive information on individuals who were in the wrong place in the wrong time, and became surveillance subjects randomly and baselessly. By their nature, secret police dossiers and informants’ reports hold sensitive and often false private information, making these public as reliable facts could involve the serious violation of personal rights.

The confidentiality of information is a matter of context, not exclusively of content.

The Blinken OSA holds information on millions of people. A once-renowned psychiatrist who left Hungary for the UK is described by Soviet authorities as a dangerous enemy of Communism. Taking his alleged opposition activity into consideration, the psychiatrist was hired by the well-known Tavistock Clinic, in London. According to samizdat publications preserved at the Blinken OSA, the same doctor was previously involved in the forced psychiatric treatment of Hungarian opposition figures. Both conflicting pieces of information are accessible in the research room of the Archives, but not online. It is the task of researchers, not the Archives, to judge contradictory information and statements.

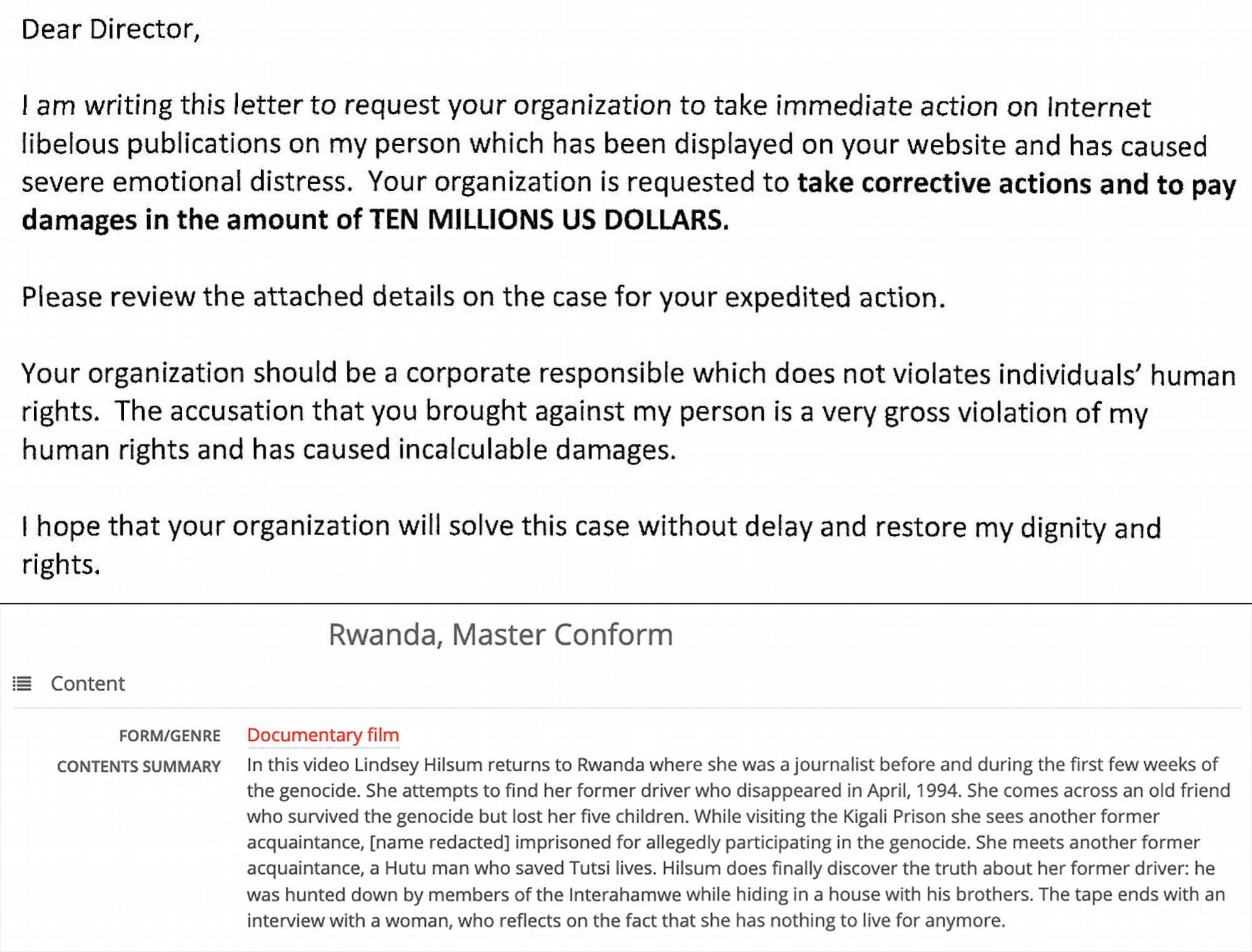

A few years ago, the Archives made the description of a BBC documentary on the Rwandan genocide available online. An imprisoned interviewee in the film says she was arrested for alleged war crimes. Soon, the Archives received a letter from the interviewee—living by then in the US—, demanding a compensation of ten million dollars for the harm (the risk of expulsion from the States) the online archival description caused to her. Although the film, including the interview, remains accessible to anyone, we decided to remove her name from the content summary.

The letter the Archives received, and the updated content summary in the online catalog.

The letter the Archives received, and the updated content summary in the online catalog.

(Blinken OSA)

The status of the archives as a place of authenticity evolved and solidified through centuries. The most crucial element in this status is trust;

trust that the institution preserves authentic documents, without changing either their content or form, i.e., their integrity, or their place among other items, and without manipulating the information, the facts the sources contain. Another significant element of this trust is, however, that citizens should be confident that their private information would not be violated, made public, or end up in wrong hands, i.e., the institution would respect citizens’ right to informational self-determination.

When making as much information available to researchers and the public as possible, the archives has to serve the public interest, yet, it also has to protect citizens’ personal rights at the same time, even if the latter means the anonymization of documents or making them accessible only to ethically responsible researchers on-site, and not available and reusable online to anyone.

Trust and archives, too, are fragile.

Similarly to a library or a museum, an archives collects the material, intellectual, artistic documents of the past in one place, for the sake of their preservation; and then come fires, floods, insects, mice, wars and revolutions, destructing the collection. Beyond physical protection, preservation also extends to processing, cataloging, conserving. Already in antiquity and the middle ages, written documents had to be copied because of their material evanescence; by mistake or for philological correction, scribes and monks often altered, adjusted texts, replaced names; the contexts of the facts changed. Nowadays, the imperfection of character recognition software is also responsible for inaccurately preserved, falsified contents. The history of medieval—primarily monastery—archives often start with massive falsifications; monks arranged, altered, manipulated donors’ donation letters, so that in exchange for prayers for the salvation of the dead, they appropriated monastery lands from living relatives. Doctoring papyrus rolls is not necessary anymore; attacking archives’ servers with a virus is enough to falsify the contents of well-secured documents, and end the trust in facts.

The entrance of Blinken OSA, in Budapest.

The entrance of Blinken OSA, in Budapest.

(Photo: Edit Baumann / Budapest100)

Archives, therefore, are in a constant and complex struggle to find balance between serving individual and at the same time—and often against—public interests; to process and preserve historical documents, and at the same time protect their integrity. The Blinken OSA, one of the largest archives related to the Cold War and human rights, launches this blog series to strengthen the trust in facts and in the preservers of facts, by sharing intriguing, relevant historical documents with the public, in a moment when the facts of the past may seem mere results of political wills.