Vera and Donald Blinken Open Society Archives

A Warning Sign: the Srebrenica Genocide Memorial

The former Bosnian Serb Army commander and convicted war criminal, Ratko Mladić's appeal hearings has begun last month. Questioning the 2017 judgement of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia is an emblematic symptom of a phenomenon increasingly present in the Balkan region; genocide denial, which, twenty years after the Srebrenica genocide, strives to downplay or even dispute the crimes committed during the Bosnian War. The process aptly illustrates the significance of institutions like the Srebrenica Genocide Memorial, where more than 6300 victims are buried and exhibitions based on archival documents recall the darkest chapter of the 1990s Yugoslav Wars. On the 17th anniversary of the memorial center in Potočari, we recommend a reading list to explore the topic.

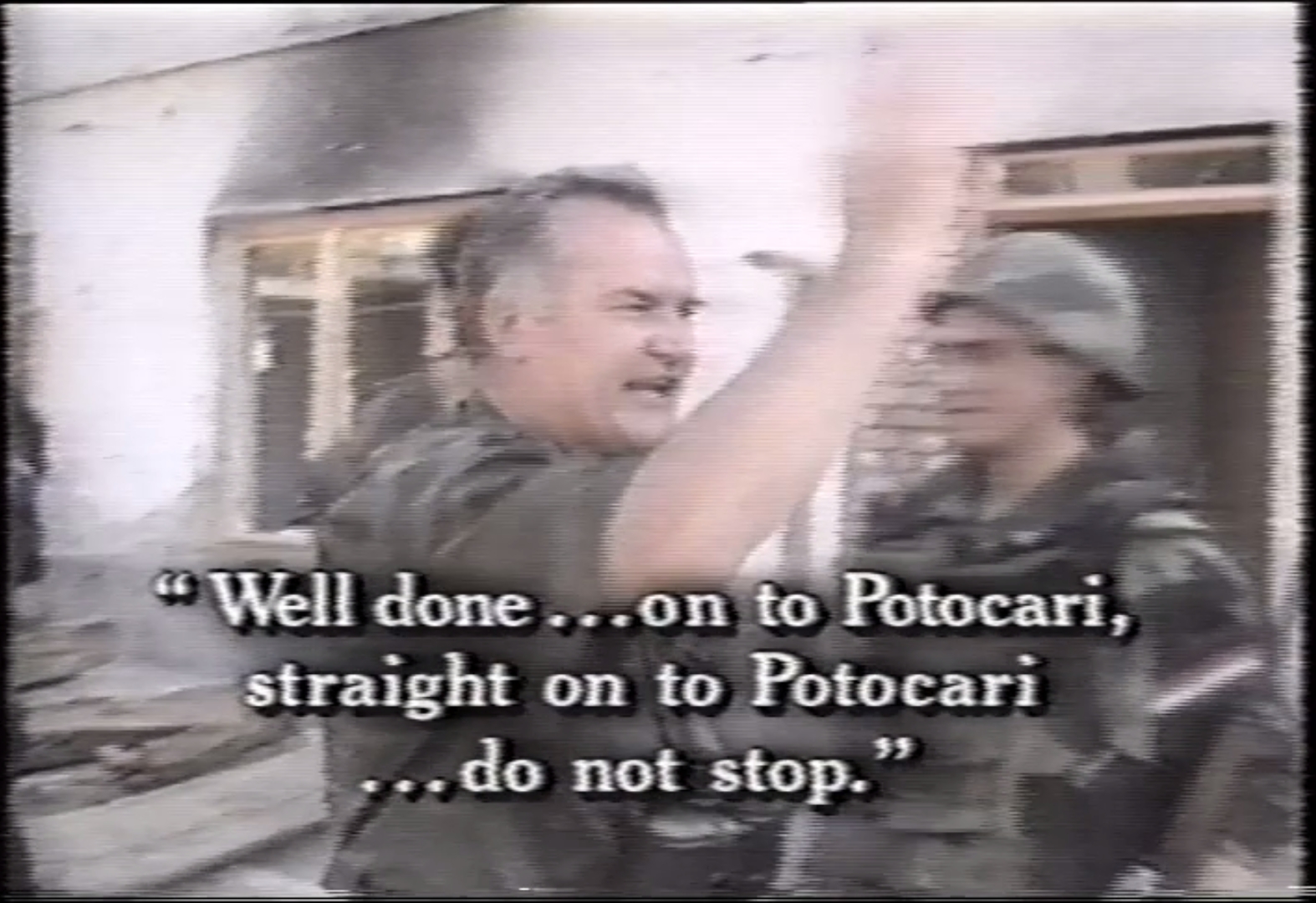

Ratko Mladić points his soldiers toward Potočari.

Ratko Mladić points his soldiers toward Potočari.

(Photo: Excerpt from ABC's Nightline. HU OSA 350-1-1:409/1, Records of the International Monitor Institute)

Dzenan Sahovic: Potočari Memorial Center and Commemorations of the Srebrenica Genocide

(in Marie Louise Stig Sørensen, Dacia Viejo-Rose, Paola Filippucci eds.: Memorials in the Aftermath of Armed Conflict, Palgrave Macmillan, 2019)

Srebrenica is a town and a municipality in Bosnia and Herzegovina's Serb entity, located close to the Serbian border. The municipality, with Bosniak Muslims as majority population, played a central role during the Balkan Wars, as its mixed population opposed the vision of a unified and ethnically homogeneous Greater-Serbia. This is what lead to the ethnic cleansing that already began in 1992, causing tens of thousands of Bosniak refugees fleeing to the enclave around Srebrenica. In 1993, the UN created a "safe area" in the territory, and established a UN base close to Srebrenica, in Potočari. However, this did not stop Serbian military attacks; on July 6, 1995, Srebrenica fell, the Army of Republika Srpska (VRS), lead by Ratko Mladić, disarmed the Dutch peacekeeping forces, Bosniak refugees were separated according to sex and age, and the systematic murder of Muslim men and boys started immediately. The news of this mass execution of more than 8000 was what finally pushed the US to launch air strikes against Serb military targets, ending the 4-year long civil war.

Dzenan Sahovic's chapter in Memorials in the Aftermath of Armed Conflict presents the process preceding the opening of the Srebrenica Genocide Memorial, and studies the institution's activities. The Dayton Agreement, ending the Bosnian War, created the state of Bosnia and Herzegovina, consisting of two entities; the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Republika Srpska. The associations representing the survivors of the genocide and the families of the victims demanded from early on to bury their dead—killed by VRS soldiers, and put in mass graves and secondary mass graves—in Potočari; however, as Potočari, just like the whole Srebrenica municipality, belonged to the country's Serb entity, such efforts were initally obstructed by the Serb population and authorities. From 1998 however, parallel to the refuge return process, commemorations began to take place at the former UN base in Potočari, which, in 2000, became the official site of the 5th anniversary. The Srebrenica Genocide Memorial was opened on September 20, 2003; 17 years ago today.

The Srebrenica Genocide Memorial: the cemetery in the foreground,

The Srebrenica Genocide Memorial: the cemetery in the foreground,

and the former UN base housing a museum in the background, to be completed soon with an archive.

(Photo: Csaba Szilágyi)

“With time, the commemorative practices at the Potočari Memorial Center are likely to change in character. Burials of victims will come to an end as most victims have now been identified and buried. This raises the question of the form that future anniversaries will take. There are, as we see it, two potential paths. On the one hand, the unresolved political conflicts between the ethnic groups might lead to an even deeper conflict of narratives about victimhood in Eastern Bosnia and an even stronger sense of Bošnjak nationalism in the yearly commemoration ceremonies. On the other hand, the passage of time and an improved political situation might slowly lead to a change of meaning of the site, moving closer to the originally envisioned idea of a site of remembrance, reconciliation, and education.”

The memorial site comprises a musem and a cemetery where each year the victims identified in the meantime are buried. The museum displays documentary films on the events, and an exhibition, opened in 2017, investigating the role of Dutch peacekeepers; a further exhibition presents personal belongings from the mass graves, thus personalizing the 8000 victims. With the professional assistance of the Blinken OSA, the Srebrenica Genocide Memorial is currently being expanded with an archive, to provide open, on-site acces to archival documents and literature on the history of the genocide and to the records and databases of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY).

The Srebrenica Genocide Memorial: ongoing construction work related to the future archive.

The Srebrenica Genocide Memorial: ongoing construction work related to the future archive.

(Photo: Emir Suljagić)

ICMP, the Srebrenica Memorial and artist Šejla Kamerić, launch art project „Forensic Archive: From One Learn All”

(International Commission on Missing Persons)

The Srebrenica Genocide Memorial commemorated the 25th anniversary, among others, by displaying a video installatation by the Bosniak artist Šejla Kamerić. On July 8 and 9, the video clips projected to the walls of the former UN base highlighted the work of the International Commission on Missing Persons (ICMP), the identification process of victims, based on the remains found in secondary mass graves. This endeavor not only provides the chance for families to bury their dead, but produces evidence of the crimes that were committed. Kamerić, who presented an earlier version of the project at Blinken OSA, combines forensic evidence and archival documents, and will turn the installation into a permanent exhibition and an expanding digital platform.

“'Despite overwhelming forensic evidence of genocide and rulings by multiple international and local courts, denial of the Srebrenica genocide persists to this day,' said Matthew Holliday, Head of ICMP Western Balkans Program. 'The use of modern scientific methods to identify Srebrenica victims establishes incontrovertible facts about the events in Srebrenica. This art installation sends the world a clear message: Facts and evidence established by science constitute a starting point for accepting the past and for building a future grounded in the rule of law. Upholding a transparent and truthful account of what happened in the past is essential for peace.'”

Šejla Kamerić's video installation at the Srebrenica Genocide Memorial.

Csaba Szilágyi: Discussion About the 1995 Srebrenica Genocide Begins in the Archives

(Blinken OSA)

Post on the Blinken OSA blog written by Csaba Szilágyi, Head of Human Rights Program at Blinken OSA, on the 25th anniversary. The fact that despite the distance of a quarter of a century, the central theme of the post instead of closure or grief is the current challenge of denialism, is an alarming sign. Szilágyi presents relevant collections preserved at the Archives, “the documents of human pain,” which, however, in the context of triumphalism, cannot become cathartic memories offering reparation, but have to keep serving as evidences in a fight against genocide denial.

“This difficult heritage is preserved and managed according to principles established by legal scholars Louis Joinet and Diane Orentlicher, according to which those who have suffered human rights abuses have the right to know the truth, and archives holding records on such abuses should be maintained and made accessible. Mass atrocity records serve as guarantees of non-recurrence of the violations they describe, and are reliable sources for understanding the nature of human rights violations and for justice-making processes. Victims and survivors have the right to reparation through preserving their memory via 'documents of human pain.'”

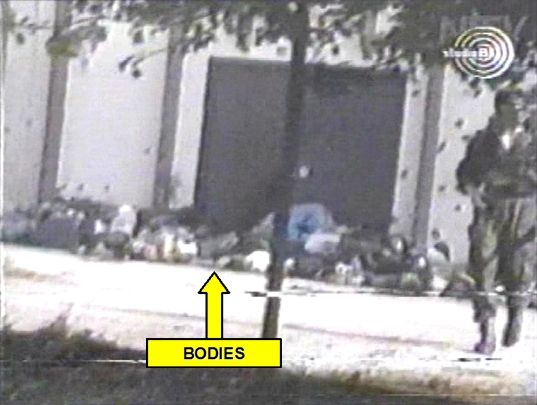

Records from the Blinken OSA holdings.

Perica Jovchevski: On Our Moral Sensibilities and the Credibility of the Nobel Committee for Literature

(Blinken OSA)

A personal remark by Perica Jovchevski, Human Rights Assistant Archivist at Blinken OSA, regarding the debate on Peter Handke's Nobel Prize in Literature. As captured by several documents in the Archives, Handke was an open supporter of Slobodan Milošević during the Yugoslav Wars, and publicly downplays and denies the Srebrenica genocide. Jovchevski argues that it is the very prestige of the prize that poses the moral demand to the Nobel Committee to consider such non-literary matters.

“The Nobel Prize in Literature enjoys the esteem not of an exclusively literary achievement, but of a paradigmatic intellectual achievement recognized worldwide. The scope of the enjoyment of this esteem is not within a specific national culture or literary community, but the universal humanity. If there is still space for the Nobel Prize not to be a 'false canonization of literature,' beside its already too long and too deep 'Western' and sexist bias, then exhibiting moral sensibility, especially in light of a genocide apology, should not be seen as an external criteria to the decision to bestow the Prize, but rather a minimum requirement for evaluating the 'ideal direction' of an outstanding work of literature.”

Emina Dizdarevic: Ratko Mladic’s Appeal Causes Anxiety for Bosnian War Survivors

(Balkan Insight / Balkan Investigative Reporting Network)

In 2017, the ICTY sentenced Ratko Mladić to life imprisonment for the war crimes he had committed. He was found guilty on ten of 11 counts, including the Srebrenice genocide, terrorizing the people of Sarajevo during the city's siege, persecuting Bosniaks and Croats throughout Bosnia and Herzegovina, and taking UN peacekeepers captive. Mladić appealed against the sentence on legal and factual grounds in 2018, his hearings has begun this August after several delays. While Mladić's defense hopes him to be acquitted, the prosecution urges him to be found guilty on the original 11th charge as well, for the genocide in six other Bosnian municipalities in 1992. The BIRN report summarizes how the international community and victims' relatives react.

“The verdict in the case against Ratko Mladic is unlikely to change the minds of political leaders in Bosnia’s Serb-dominated entity Republika Srpska and in Serbia, where the classification of the Srebrenica massacres as genocide is firmly rejected. But for Mirsada Malagic, whose loved ones were killed in the July 1995 massacres, a conviction for Mladic would forever stand as a warning to others. 'All those who might even think about doing the same thing, they would know that justice will catch up with them,' she said. 'That is what the verdict would mean to me.'”

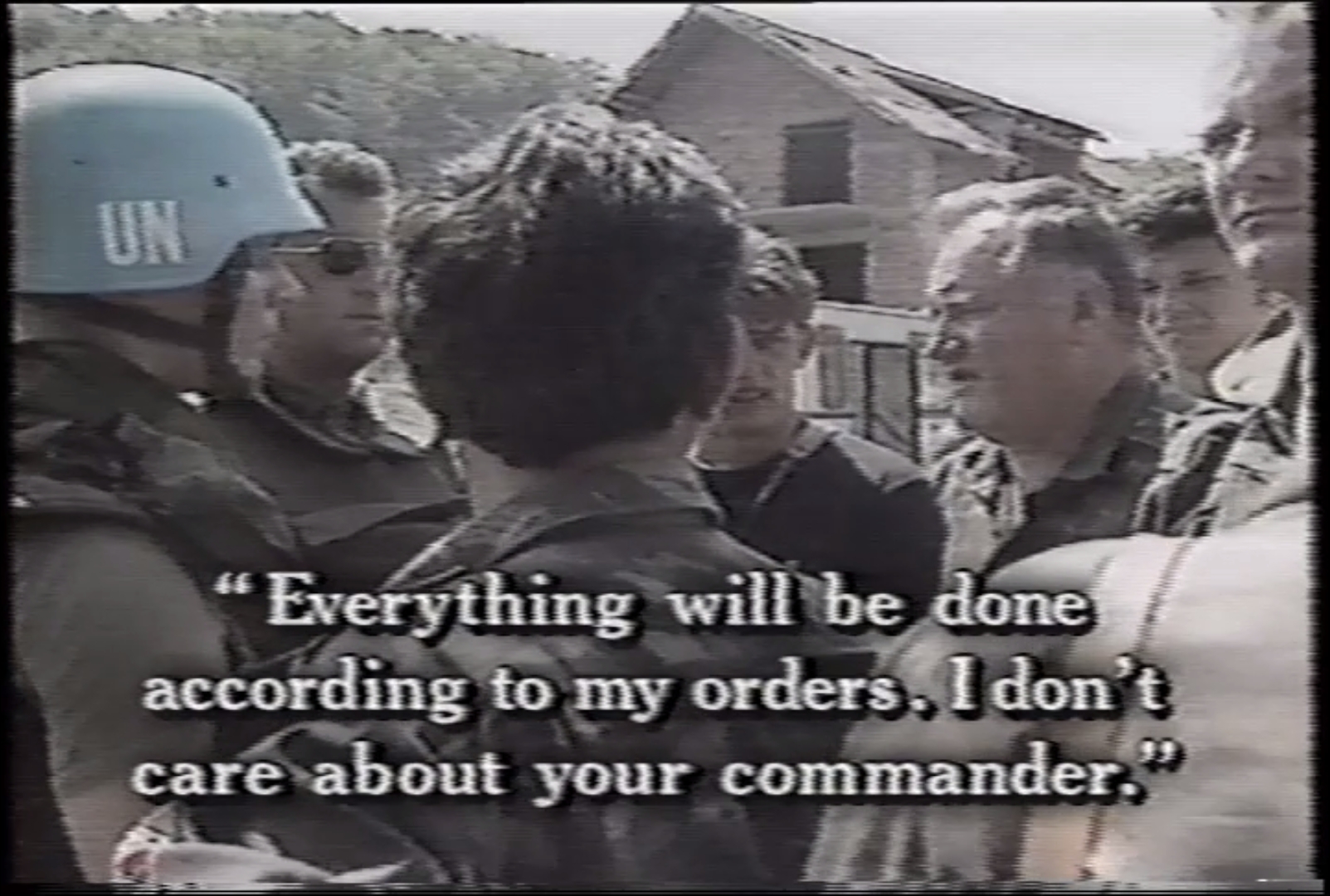

Ratko Mladić talking to disarmed UN peacekeepers.

Ratko Mladić talking to disarmed UN peacekeepers.

(Photo: Excerpt from ABC's Nightline. HU OSA 350-1-1:409/1, Records of the International Monitor Institute)

Julian Borger: Srebrenica 25 Years On: How the World Lost Its Appetite to Fight War Crimes

(The Guardian)

Julian Borger, world affairs editor at The Guardian, revisits the history of international tribunals on genocides. The UN establised the first such international criminal courts to bring justice concerning the war crimes committed in former Yugoslavia (sentencing 90 people) and Rwanda (sentencing 93). Borger links these courts to the spirit of the Nuremberg and the Tokyo trials, and describes them as devoted efforts against mass atrocities. Today, however, power relations seem to shift; in 2020, as the International Criminal Court faces attacks from the US president, Syrian war criminals were sentenced in Germany not by an international, but, for the first time, by a regional court.

“A quarter century on from Srebrenica, the world has become painfully used to atrocities. Mass killings in Syria or Yemen no longer always make the news. China has incarcerated more than a million Muslim Uighurs and forced contraception, sterilisation and abortions on them.”

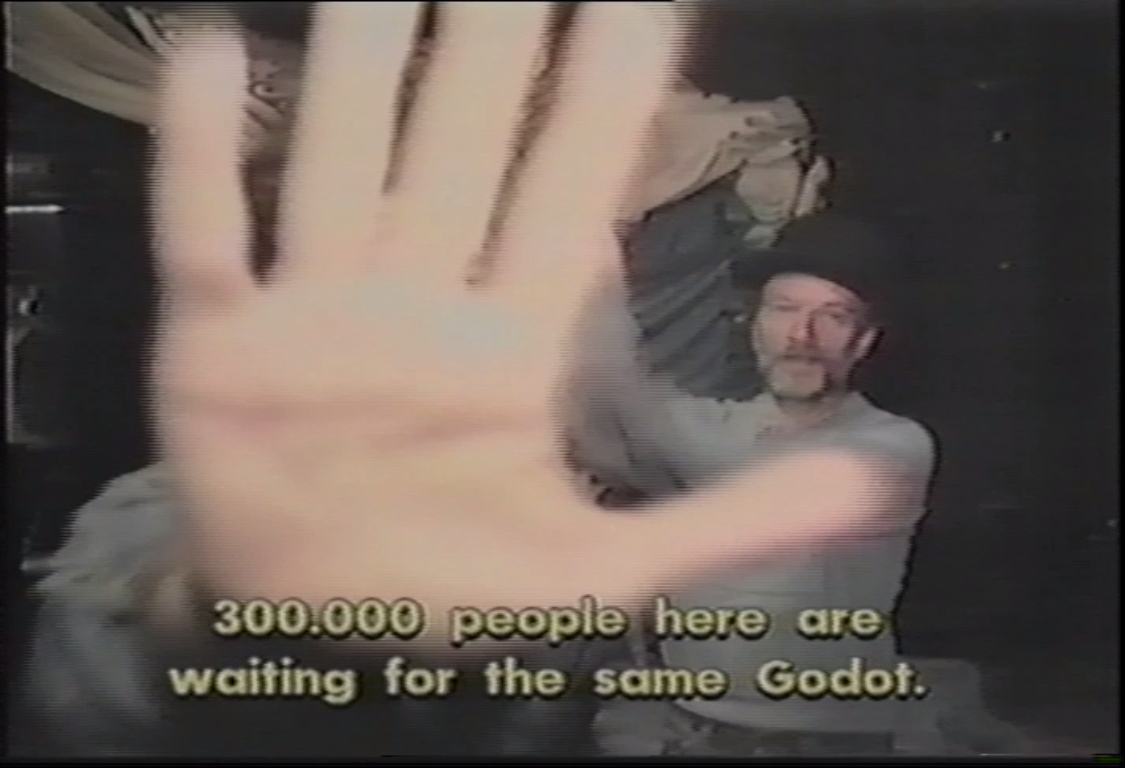

Susan Sontag: Godot Comes to Sarajevo

(The New York Review of Books)

From April, 1993 on, Susan Sontag visited Sarajevo 11 times, as recounted by Benjamin Moser; a film entitled Godot Sarajevo, available at the Archives, also captures her stays in the city. In the latter, Sontag explains her presence with the intention to do something “with people here, for people here.” As Sarajevans, trapped in a city sieged by the VRS, were waiting for Western intervention, she staged Brecht's Waiting for Godot. The film is primarily revolved arond the play, but also follows and interviews the involved actors, owing to which the rehearsals are often disrupted “by tactics of survival, including fetching water and woods.” Sontag called international attention to the genocide in Bosnia and Herzegovina already in 1993, two years before Srebrenica. During her visits she experienced the mechanism she studied in her essays on war aesthetics and the images of pain; “to go to Sarajevo now is a bit like what it must have been to visit the Warsaw Ghetto in late 1942,” she noted in a letter to a friend.

“This is the first of the three European genocides of our century to be tracked by the world press, and documented nightly on TV. There were no reporters in 1915 sending daily stories to the world press from Armenia, and no foreign camera crews in Dachau and Auschwitz. Until the Bosnian genocide, one might have thought—this was indeed the conviction of many of the best reporters there, like Roy Gutman of Newsday and John Burns of The New York Times—that if the story could be gotten out, the world would do something. The coverage of the genocide in Bosnia has ended that illusion. Newspaper and radio reporting and, above all, TV coverage have shown the war in Bosnia in extraordinary detail, but in the absence of a will to intervene by those few people in the world who make political and military decisions, the war becomes another remote disaster; the people suffering and being murdered there become disaster 'victims.'”

(Godot Sarajevo, dir.: Pjer Žalica. HU OSA 350-1-1:172/1, Records of the International Monitor Institute)

(Godot Sarajevo, dir.: Pjer Žalica. HU OSA 350-1-1:172/1, Records of the International Monitor Institute)