Vera and Donald Blinken Open Society Archives

The Memory of the Holodomor in Ukraine: A Dissonant Heritage that Haunts the Presence

Until the early 1990s, the Great Ukrainian Famine of 1932–1933, known today as the Holodomor, belonged to the most repressed topics in Ukrainian and broader East European history. Denied by Soviet authorities and downplayed by the international public, the famine was not a topic of systematic academic research. While Ukrainians living in the diaspora were free to commemorate victims, raise monuments, publish books, and gather testimonies from survivors, those who stayed in Soviet Ukraine were covered by a veil of silence. No commemorations, publications, and even talks on the topic was possible. As the memory of the Holodomor in contemporary Ukraine remains scattered and fragmented, its study requires a complex approach that combines archival research with ethnographic observations and interviews.

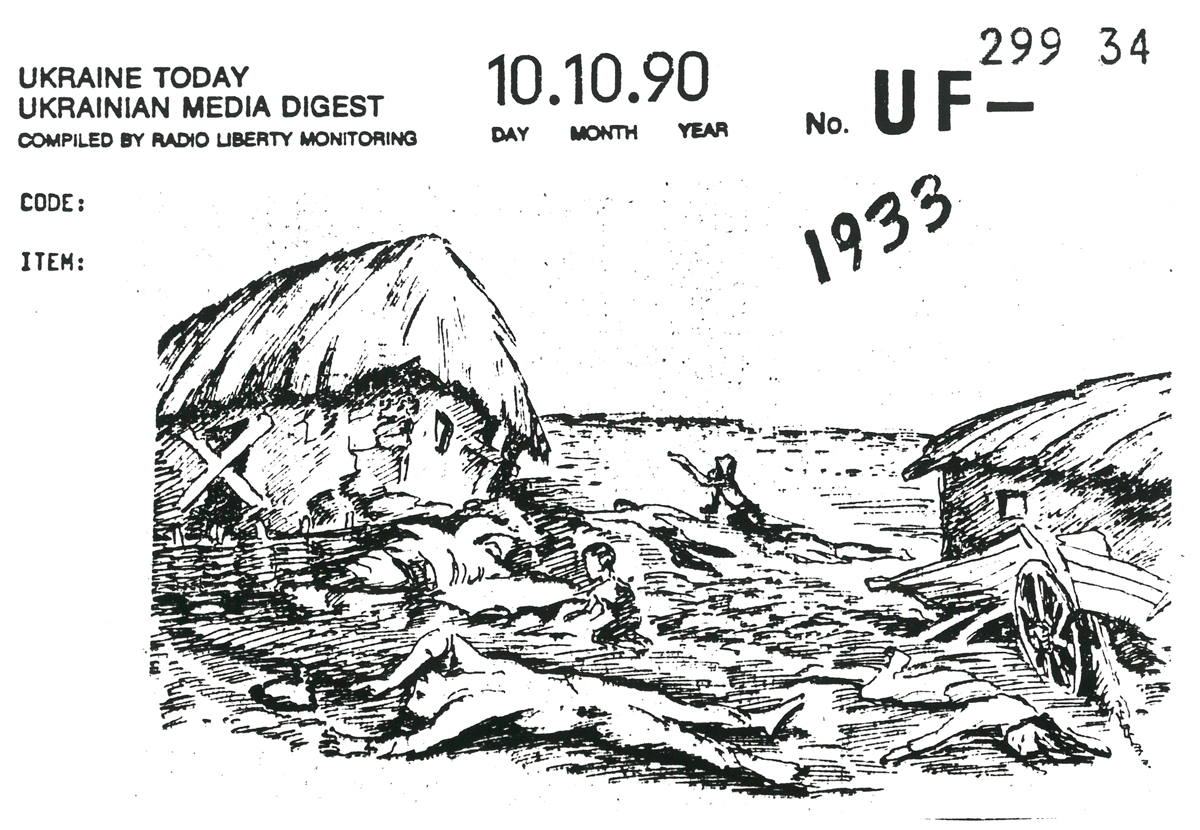

Excerpt from RFE/RL’s Subject File on the Holodomor.

Excerpt from RFE/RL’s Subject File on the Holodomor.

(HU OSA 300-81-2 Records of RFE/RL Research Institute, Monitoring Unit, Subject Files Related to Ukraine)

The Great Ukrainian Famine in 1932–1933 was one among many famines that developed across the Soviet countryside as a result of the rapid modernization and collectivization of agriculture implemented by Stalin’s first Five Year Plan of 1928–1933. Recent demographic studies estimated the Holodomor death toll at 3.9 million direct losses. However, in the USSR, the destruction and fabrication of documents pertaining to the 1930s were important tools in hiding and denying political violence. The case of the collectivization famines, and the famine in Ukraine in particular, was not different. Millions of peasants that perished in 1932–1933 did not leave material traces in Soviet archives. State records and official statistics silenced their suffering, denied their deaths; the starving were called as “anti-Soviet provocateurs.” People could not mourn their deceased relatives, the topic never entered school curricula. That is why the material accumulated at the Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, in Munich, provide a window to understand and counter these dynamics of the state-induced erasure memory. When in the 1980s, the cultural memory of the famine slowly emerged, the RFE/RL staff strived to collect every appearance of the topic in local newspapers. As a result, the radio’s Research Institute gathered a collection of more than 100 clippings from the Soviet Ukrainian press related to commemorations in the late 1980s, preserved today at the Blinken OSA Archivum. Across the political and cultural spectrum, newspapers such as Literaturna Ukraina, Silski Visti, Ukraina, Kultura i Zhytja, Visti z Ukrainy, Vitchyzna, or Radianska Ukraina documented local memorial events, published memoirs from famine survivors, and called for rewriting Ukrainian history. Knowledge of the famine gradually resurfaced in the public sphere.

In the late 1980s, analysts at RFE/RL were particularly interested in the activity of Volodymyr Maniak, a prominent Ukrainian writer and journalist, one of the most influential figures in bringing to light memories of the famine. In 1988, together with his wife, Lydia Kovalenko, he initiated a project to gather written testimonials. Shortly, they received thousands of responses. Compiling these accounts, the commemorative book, Holod 33-y: Narodna knyha-memorial (The famine of 33: A people’s memorial book) was published in 1991. At the same time, the Institute of Party History of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine approved two other publications. The first was a selection of documents from the newly opened archives, Holod 1932–1933 rokiv na Ukraïni: ochyma istorykiv, movoiu dokumentiv (The famine of 1932–1933 in Ukraine: Through the eyes of historians and the language of documents), published in 1990; the second was a socio-economic analysis of the famine by Stanislav Kulchytskyi. Paradoxically, the state that not so long ago blocked any knowledge and closed its archives was now supporting and organizing the first publications on the famine.

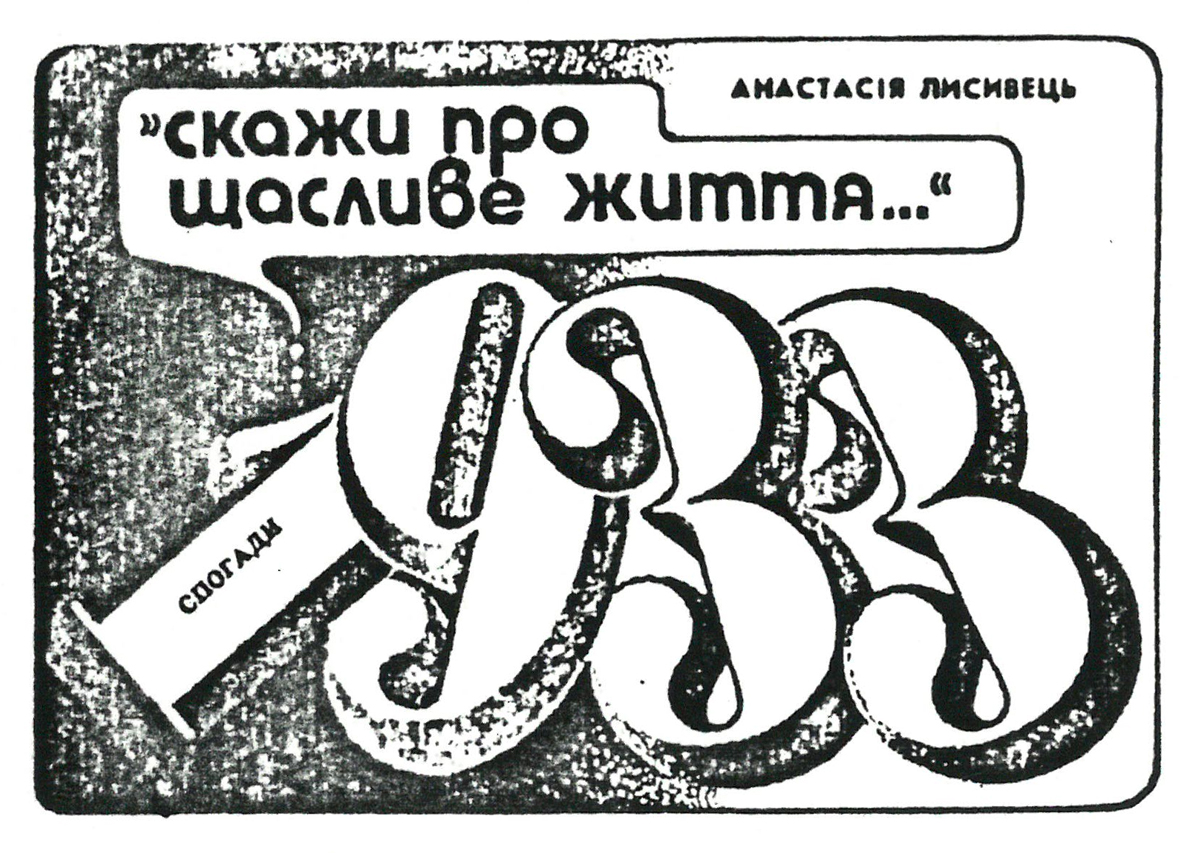

“Speak of the Happy Life” – The memoir about the Holodomor written by Anastasia Lysyvets in 1976 was published in the journal Vitchyzna in 1989. Its English translation was published in 2022

“Speak of the Happy Life” – The memoir about the Holodomor written by Anastasia Lysyvets in 1976 was published in the journal Vitchyzna in 1989. Its English translation was published in 2022

titled The Holodomor and the Origins of the Soviet Man: Reading the Testimony of Anastasia Lysyvets.

(HU OSA 300-81-2 Records of RFE/RL Research Institute, Monitoring Unit, Subject Files Related to Ukraine)

In the 1980s, memoirs, testimonies, and the calls to rewrite the Soviet past were not the only channels through which knowledge of the famine resurfaced. Even more critical were local commemorations that gathered people around feelings of loss, grief, and the need for historical justice. RFE/RL reported extensively on numerous such events organized across the Ukrainian countryside. In the village of Kohanivka, Cherkasy Oblast, a note briefly announced the creation of a memorial to the “Martyrs of Hunger Death of 1933” that was initiated by the village teacher and further financed by the inhabitants. In Tagran, Kyiv Oblast, the commemorations brought together eyewitnesses, Ukrainian dissidents, and historians. One of them was a prominent writer, Ivan Drach, who admitted publicly, probably for the first time, that both his grandfathers died in “this horrible holodomor of 1933.” As he explained, “In Telizhenec, half of the cemetery belongs to those who perished by hunger… there are dozens, hundreds, thousands, millions of people.”

While touring central Ukraine in the summer of 2019, I’ve found the material remnants of many similar gatherings as the ones described by RFE/RL. Burial mounds marking mass graves of the starving, forgotten crosses on the sides or roads, small memorials and tombstones decorated with flowers stood as remarkable evidence of these early commemorations. Created by and for the villagers, they demonstrate a local need to mark a history that had, until recently, remained hidden from the public gaze.

Burial mound in Yasenivka, 2019.

Burial mound in Yasenivka, 2019.

(Photo by the author)

In the village of Yasenivka, the site of mass grave was marked by a mound of significant size with a blue cross and artificial flowers on top of it. Yasenivka was one of the smallest villages I passed through, just a couple of houses on both sides of the main road. Furthermore, the cemetery was small, with a few graves evenly spread out. The mass grave, however, was one of the biggest I’ve seen, suggesting the vast human toll of the famine in what probably used to be a larger village. In the area, many villages were blacklisted and isolated; with time, they disappeared from the map as well as the landscape. Many others had drastically shrunk in size; Yasenivka was one of these.

In many of the places I visited, the sites of these early commemorations have remained untouched since the late 1980s. Simple burial mounds, crosses on the sides of roads, and small memorial plaques were the most popular mnemonic forms. In some places, the mass burial sites from 1932–1933 were overgrown by bushes or hidden in the forests. However, there were also sites with more impressive granite plaques and tombstones. In most of these, villagers organized themselves, collected funds, and created small monuments or crosses that mark previously unidentified mass graves.

Memorial complex in Sabadash, 2019.

Memorial complex in Sabadash, 2019.

(Photo by the author)

In the village of Sabadash, a unique memorial was dedicated to a particular person, Samson Efrem Bachinsky, the head of the collective farm, who “saved people from starvation in 1932–1933.” Located next to the burial mound, this newly-erected memorial suggested that the memory of the famine was still vivid in many communities. Moreover, a desire to commemorate local leaders became apparent. As the head of the collective farm, Bachinsky manipulated the procurement plans and bargained in the oblast over the impossibility of fulfilling them; which, in reality, meant hiding food resources from search brigades, or preventing the latter from committing violent searches.

During my fieldwork in Ukraine, I talked with local historians and teachers who, in the 1980s, collected testimonies from survivors. As they all admitted, documenting the memories of the famine, such as the ones about Bachinsky, was one of their most challenging tasks. Only a few people wanted to talk with them. As one of the historians recalled, “They thought I was esbeushnik [a secret police officer]. Everyone ran away from me.” Only after a while did he convince locals to talk with him about what they called the “hungry days.” He showed me piles of notebooks and folders of transcribed and cataloged testimonies. As he pointed out, “In the late 1980s, something changed. Somehow people were willing to talk about their experiences. So, again, I went to every village and asked the oldest inhabitants whether they remembered the names of those who perished in 1932–1933.” Thanks to the activism of these local historians and teachers, the first statistics of famine deaths were brought to light. The small plaque in the villages I visited read, Oleksandrivka: 399, Sokolivka: 370, Zhytnyky: 504 famine deaths. None of the numbers were final and confirmed. They were all based on local recollections of the villagers.

Memorial dedicated to the victims of the Holodomor in Zhythnyky, 2019.

Memorial dedicated to the victims of the Holodomor in Zhythnyky, 2019.

(Photo by the author)

As thoroughly documented by Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, these local commemorations changed what was accepted as historical truth in the 1980s. They marked the eventual democratization of public discourse, shifts in the attitudes toward the Soviet past, and, perhaps most importantly, stressed the role of the press in shaping the transition. At the same time, local commemorations revealed the vast scale of collective grief felt by affected communities. The collective memory of the famine was hidden away in people’s homes and patiently waited to resurface. In 1932–1933, the famine broke the peasantry and contributed to the Sovietization of the Ukrainian countryside. In the 1980s, the memories of the famine helped to open and democratize the same spaces.

The growing number of these local and bottom-up commemorations spurred the debates regarding the creation of a national monument commemorating the victims of the famine. On January 4, 1990, the prestigious journal Literaturna Ukraina published an appeal by the writer Oleksij Kolomyjec. As the editors stated, four months later, they received many supportive letters, yet it was unclear if where the memorial site was supposed to be. Politicians quickly jumped on the idea and instrumentalized it for their political goals.

One of the most publicized commemorations of the famine took place on July 12, 1990, in Lubny, Poltava region. On that day, a big crowd gathered to witness the marking of the site for a future memorial to those who died from the “horrible starvation of 1932–1933.” Famine survivors were joined by writers, historians, activists, and high-ranking church officials. However, one of the first to speak was Maria, an elderly pensioner who experienced the holodivka as a child. She reflected, “We came here with my sister and fellow villagers. This will be our sacred place. Our mother died from hunger; our father was arrested… Today, people do not understand what it means, when you are 12 years old, and you have only a small piece of bread.”

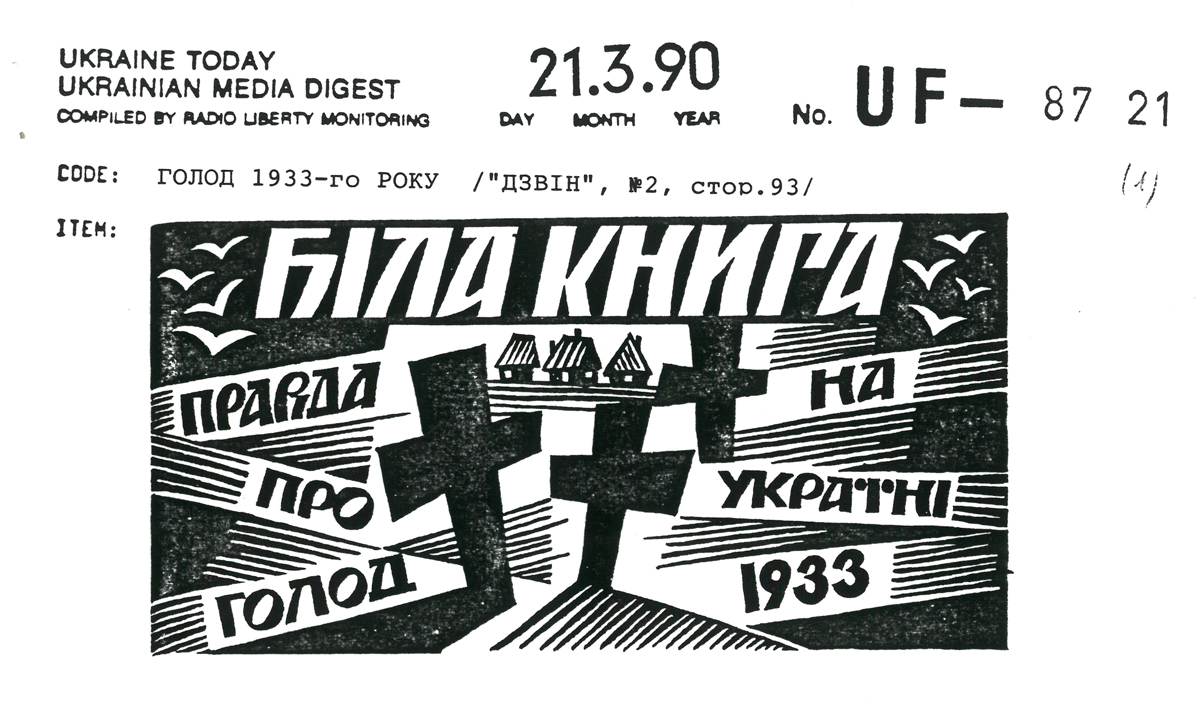

“The White Book: the truth about the famine in Ukraine, 1933” – Recollections about famine, published in the journal Dzvin in 1990.

“The White Book: the truth about the famine in Ukraine, 1933” – Recollections about famine, published in the journal Dzvin in 1990.

(HU OSA 300-81-2 Records of RFE/RL Research Institute, Monitoring Unit, Subject Files Related to Ukraine)

Following Maria were political leaders and historians who stressed the need to create a national monument as a pilgrimage site for all Ukrainians. One of them was Leonid Kravchuk, then the chairman of the Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian SSR, a future president of independent Ukraine. The presence of Kravchuk at the event might have surprised many, as a few years earlier he had been the head of the Propaganda and Agitation Department of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine and was most likely supervising counter-propaganda efforts, including Operation Pharisee, designed to debunk the anti-Soviet campaign by “Ukrainian nationalists” abroad. However, in the early 1990s, the political climate was different, and Kravchuk quickly realized the ideological potential of the famine as a symbol. As he stated in his short speech:

“Dear people! Eyewitnesses who survived the 1930s, sons, daughters, and grandchildren of those who died from starvation! Today, we are erecting a monument to the victims of the tragedy, the victims of the Holodomor. This monument will be made not from stone, not from bronze, but from earth. Earth that gave birth to our nation and the earth that took those who died of hunger… Today, we know who was guilty—Stalin and his comrades. But we, the Ukrainian nation, are free and on our path to independence and self-determination. There is no turning back. People will come here not only to pay respect but to follow the path toward independence.”

Memorial complexes in Stavyshche and Volodymirivka, 2019.

Memorial complexes in Stavyshche and Volodymirivka, 2019.

(Photos by the author)

Kravchuk’s speech was one of the first public statements to introduce “holodomor” into the official Ukrainian political vocabulary; two years later, it would be widely recognized and used by politicians and the public. The speech set the famine as a form of a national myth that brought the people and the land together regardless of their ethnic background. Kravchuk used the famine for his self-legitimation by condemning Stalinism; clearly, as a leader who had pursued his career within the party structure, he could not mention Communism. Soon, Kravchuk authorized the opening of the archives and the publication of the first collection of documents demonstrating the totalitarian past of the Ukrainian SSR.

For former Soviet politicians like Leonid Kravchuk, the famine became a potent symbol for distancing themselves from their Soviet pasts, serving their nationalizing goals. As the local waves of commemorations demonstrated, many still felt the tragedy and were trying to come to terms with their past. Starting from Kravchuk, the first president of independent Ukraine, famine commemorations were raised to state level. On the 60th anniversary of the famine, Kravchuk participated in the conference The Holodomor in Ukraine, 1932–1933: Causes and Consequences, and expressly called the famine genocide, and articulated the need to start an international campaign for the official recognition of the Holodomor. Within a few years, the cultural trauma of famine was used to unite Ukrainians and further distance them from Russians and their common Soviet past. The opening of the archives, the publication of new books, and the gathered testimonies played a paramount role in showing the path toward self-determination to newly-independent Ukrainian society. In 2008, on the 75th anniversary of the tragedy, the National Museum of the Holodomor-Genocide opened in Kyiv and inaugurated new waves of commemorations nationwide. Together with the Bitter Memory of Childhood, a haunting statue of a young girl with a handful of wheat stalks, the memorial complex became a national symbol of Ukrainian collective victimhood under the Communist regime. Still, many of these national actions were also export-oriented, delineating a distinctively Ukrainian history for the international public.

The sculpture Bitter Memory of Childhood, with the National Museum of the Holodomor-Genocide in the background.

The sculpture Bitter Memory of Childhood, with the National Museum of the Holodomor-Genocide in the background.

(National Museum of the Holodomor-Genocide)

Many affected communities, however, were left to themselves. The village-level commemorations remained in the hands of villagers, local activists, and civil society organizations with little support from the government in Kyiv. Soon, the wave of these early bottom-up commemorative actions—captured by Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty in the late 1980s—disappeared from public consciousness. The politicization and nationalization surrounding the Holodomor, and the various “memory wars,” created a dissonance toward the heritage felt by many to this day. The complex history of the famine became an (unwanted) legacy haunting the uncertain present and future of Ukraine.